-Boria Majumdar

When Brazil last won the title in 2002, this is how the victory was reported in the Kolkata press the next day, “India didn’t play in the world cup. But they won it on Sunday night on the streets of Kolkata. ‘Bra..aazil’ – some sang others shouted and still others hugged friends in delight. One man – a wizard called Ronaldo – had made their day. Kolkata celebrated Brazil’s record breaking fifth world cup victory as if there was no tomorrow, living up to its reputation of being a true soccer crazy city. Their faces painted yellow and green, men and women danced in the aisles and on the streets in unmitigated glee. From Netaji Indoor stadium, where thousands watched the match on a giant screen to Bosepukur, Sealdah, Bhowanipore and Rashbehari, the Samba kings ruled. ‘Jai bolo guru Ronaldo holo boss’, (Hail Ronaldo, he is the king) said a woman who came to sell muri-badam3 outside the stadium. Kolkata’s love for Brazil was inexplicable but ubiquitous. Without exception, the two sexes stood in unison saluting the best team in the world. For the moment, Kolkata had become the second capital of Brazil.”

It is no surprise then that the city is be rooting for Richarlison and Tite as Brazil takes field against Switzerland in Qatar trying to win a record 6th title. And if they do, we could well see a repeat of what happened in Kolkata.

For one who has grown up in Kolkata, and has been witness to the football crazy nature of the city for years, these scenes were natural, they have been replicated over and over again in the course of the last two decades. Every Brazilian victory has been cheered and every defeat has left the city in a state of gloom. Why is it that fans in Kolkata mourn a Brazilian loss in football just as they mourn an Indian loss in cricket, and why is it that Kolkatans feel this way about players who hardly know a thing about their football?

Given the nature of the histories of Kolkata and Brazil – the inhabitants of both had been subject to exploitation – it is natural for the Kolkatans to prefer Brazil to other European powers. Having served as a British colony for almost 200 years, 1757–1947, Bengalis are, naturally, averse to supporting a football team of their former colonial masters, England, France, Holland or Germany. This explains why, in the opening match of the 2002 World Cup between defending champions France and Senegal, almost all Bengalis cheered the latter, who were once a colony of the French. Just as in India, where cricket and Hindi films are perhaps the only symbols of national unity, in Brazil too, football is much more than an obsession: it is justly designated the country’s ‘official religion’. Further, as in

Kolkata, where a loss in cricket to arch rivals Pakistan is perceived as a national calamity, in Brazil, anything less than the title of world champions is a national disaster. In the Brazilians, the Bengalis find their non-white clones, who can meet their dream of meeting the imperialists and neo-colonialists head on.

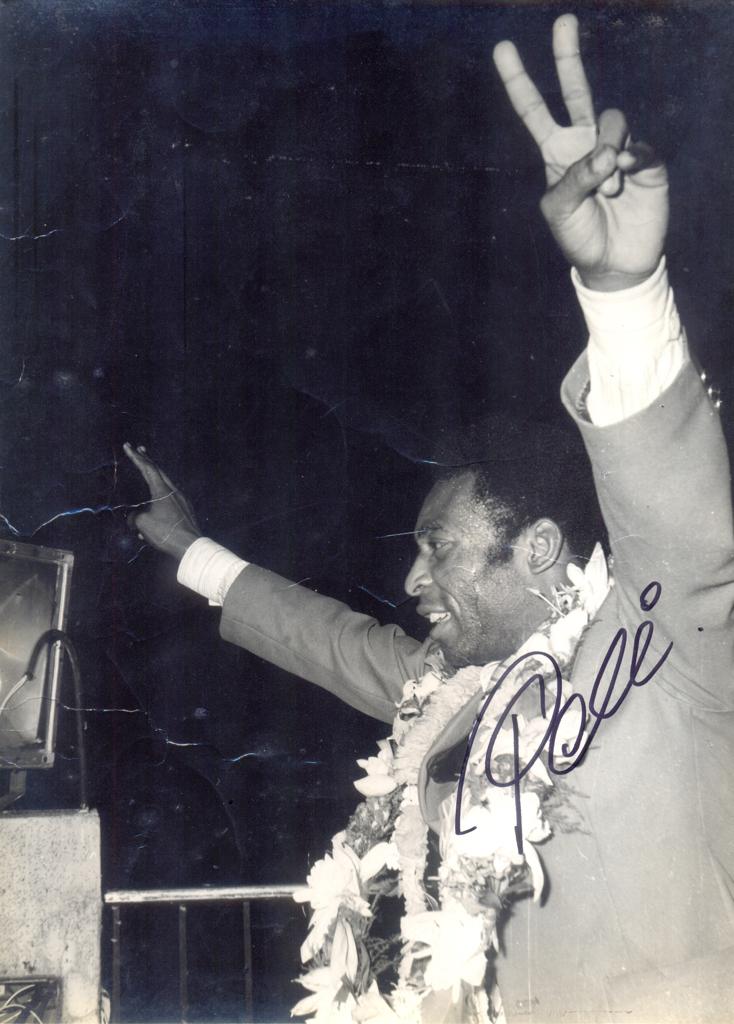

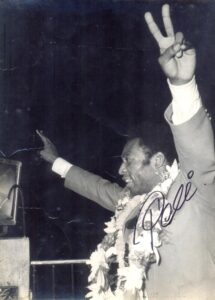

Furthermore, Brazilian football, traditionally a working class sport, is something the masses in Kolkata can identify with. Unlike Europe, where football is a full-fledged industry and academies and schools oversee the nurturing of talent, in both Brazil and Kolkata, given their economic conditions, such infrastructure is unthinkable. Unlike European stars – products of a sophisticated European football nurturing system – Brazilian stars learn by playing in the streets and local parks and in most cases make their way to the top by relying on exceptional talent alone. Scientific training, proper diet, systematic physical drills, part of the European footballing experience, has made Europe alien for most countries of South Asia. By contrast, Brazilian football involves skill, stamina and passion, attributes the working classes in Kolkata possess. With most Brazilian stars, who are soaring from lower middle class households to become world icons, the poor, underprivileged young man in Kolkata, in attempting to emulate them, can still dream of conquering the world with his limbs alone. Add Pele’s visit to Kolkata in 1977 and you will know why Prasun Bhattacharya, the poor, hard working, small town boy in the much acclaimed Moti Nandi novel, Striker, dreams of the Secretary of the Santos Football Club offering him a contract, having come all the way from Brazil.