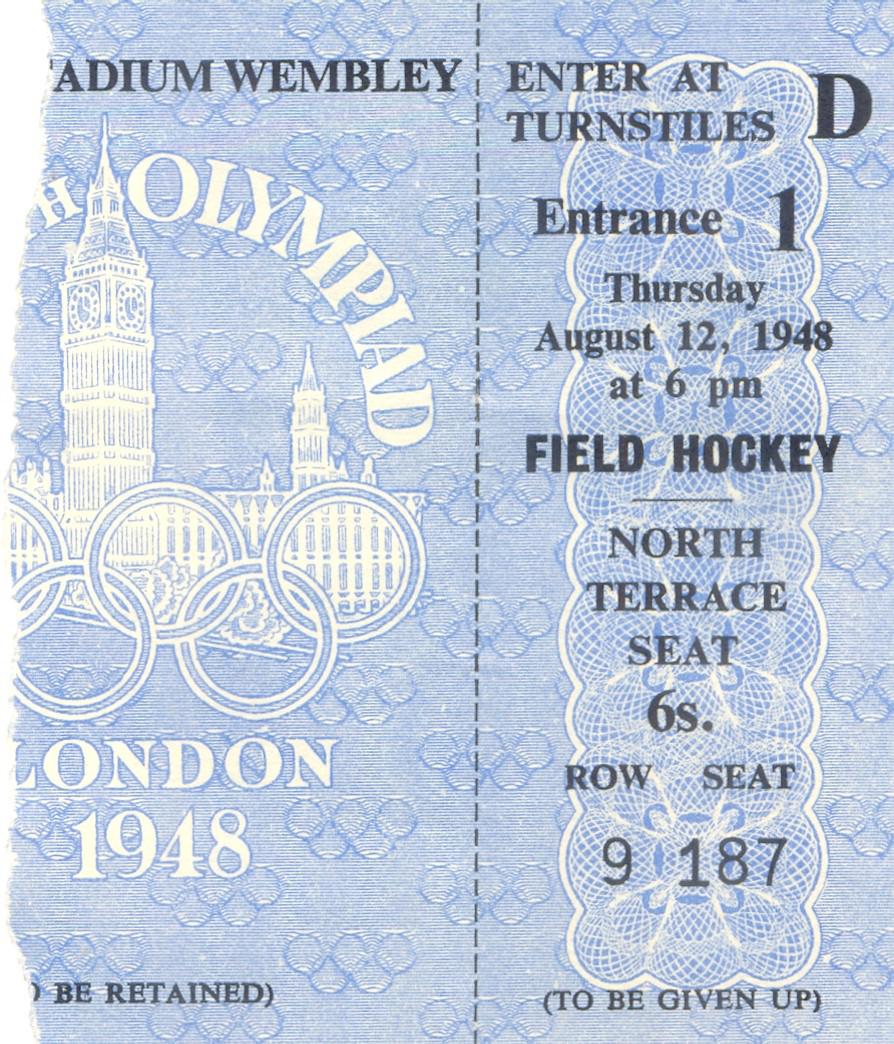

It was the dream final: Newly independent India, the defending champions from 1936, taking on Great Britain, their former imperial masters who had avoided playing Olympic hockey as long as India remained a colony.

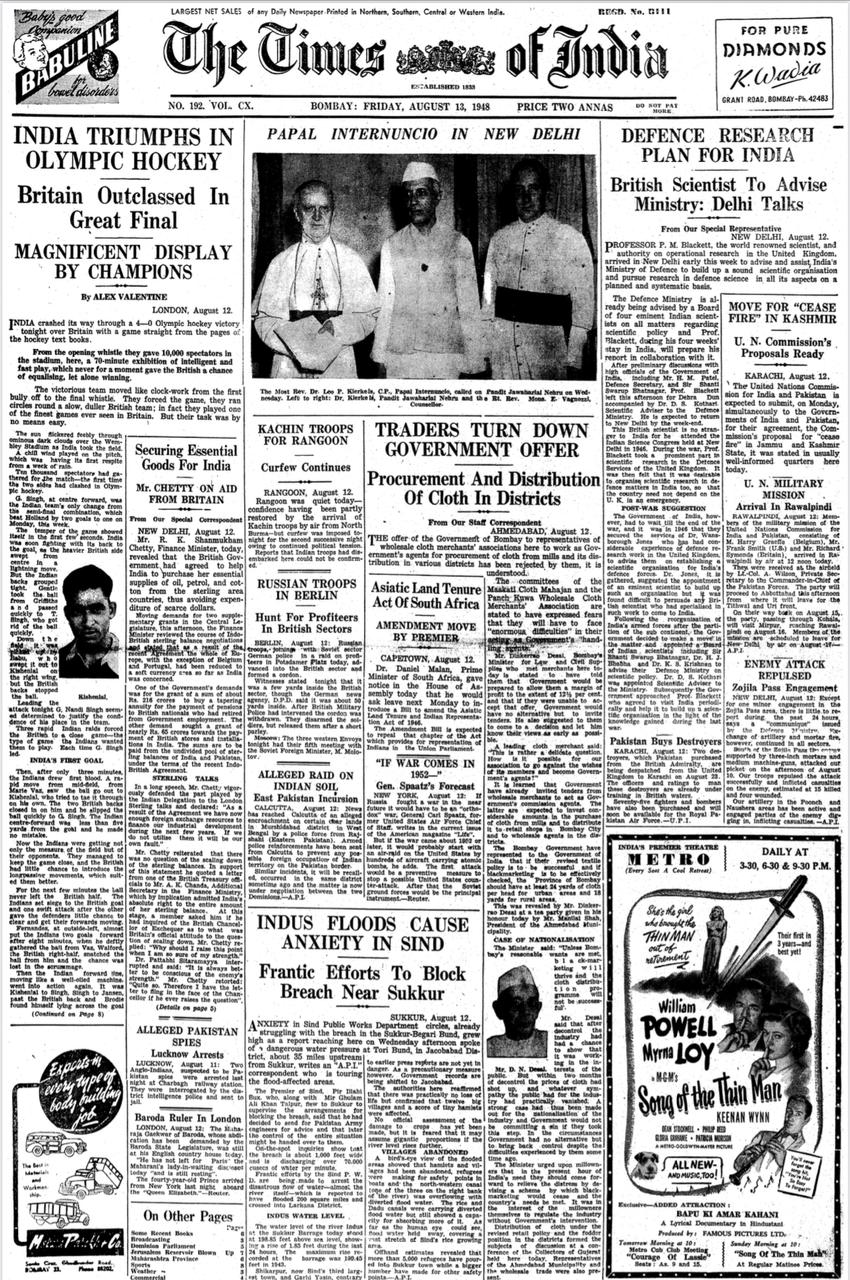

That the Indians were aware of the symbolic significance of the challenge was evident from a report filed by Alex Valentine in The Times of India of August 12. He declared that the Indians had decided not to play any further practice matches but had started a two-day ‘armchair strategy’ session in preparation for the final. ‘The chief factor in Thursday’s final, readily recognised by both sides, will be the weather. The Indians want hot sunshine for the next two days, the Britons want rain, or at least no heat.’

That the weather had already tilted the balance in favour of the British was borne out when the groundsman in charge of the pitch declared in jest, ‘A heat wave between now and the final will not leave the pitch much harder than what it is now.’

When it poured on the eve of the final on August 11, most of the Indian players decided to take the field in studded boots instead of playing barefoot. Also, they were aware of the extra sporting connotations of the contest, a fact evident from the following statement by Balbir Singh Sr: ‘Britain had been Olympic hockey champions in the 1908 Games at London, and in the 1920 Games at Antwerp. Once India made their entry in the 1928 Games at Amsterdam, they decided not to play. Britain never played an India XI as long as they remained our rulers. The 1948 Olympic hockey final was the first meeting between Britain and India.’

Despite the odds being firmly stacked against them in the final, India won the battle in style, defeating Great Britain 4–0. The overwhelming Indian superiority was borne out in the match report by Alex Valentine in The Times of India:

“India won the 1948 Olympic Hockey Championship in decisive fashion at the Wembley Stadium tonight, defeating Great Britain by four goals to nil. India’s superiority was never in dispute. Despite the heavy, muddy turf and the light rain, which fell for considerable time during the game, the Indians outclassed the British team with their superb ball control, accurate passing and intelligent positional play. Long before half time it was evident that India should win comfortably. If England had had any other goalkeeper but Brodie, India might have doubled their score…(By the middle of the second half) Britain had resigned to the fact that they had lost the game. But they were determined not to lose it by a greater margin. Whatever energies they had left they put into their defence. As the minutes dragged to the closing whistle, it was apparent the Indians were not going to get through the wall of British defenders. Full time came with yet another Indian attack on the British goal—and the match closed as it had opened. Only now the Indians were four ahead.”

This victory, achieved on British soil, unleashed some of the wildest celebrations Indian hockey had ever known. To give a cricketing analogy, most Indians today remember the delightful Indian invasion at Lord’s after the victory in the 1983 World Cup final. The images of those celebrations, beamed live on television, are now etched forever in India’s collective memory. There were no live cameras to record the landmark hockey win in London for posterity, but contemporary press reports noted that the few thousand Indian spectators present were delirious. Amidst spectacular scenes of jubilation, VK Krishna Menon, the Indian High Commissioner, ran on to the ground to join the celebrations. Reviled by Western, and especially American, diplomats, even the stern Menon – ‘the devil incarnate’, ‘Mephistopheles in a Saville Row suit’, ‘the old snake charmer’ – who was to later ‘bore’ the United Nations with his marathon seven-and-a-half-hour speech on Kashmir, let his hair down that day.

As Balbir Singh Sr reminisced, “After the victory, VK Krishna Menon, free India’s first High Commissioner in London, came running to congratulate us. He joined us for a group photograph. Later, he also gave an official reception at India House, where a big gathering of sports lovers was present. The Olympics over, we went to the European mainland and visited France, Czechoslovakia and Switzerland. This brief tour, a fortnight in duration, was more of a goodwill nature, and earned India a great deal of fame. None of us had visited Europe before, and we were thrilled by the sights we saw.”

On their return to India, a red-carpet welcome was given to the team. The victory celebrations continued for several days and climaxed in Delhi, where Rajendra Prasad,the President, and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru attended an exhibition match involving the Olympic team at a jam-packed National Stadium. Balbir Sr was hailed across the nation for his two goals and feted as the new star in Indian hockey. The victorious team of 1952 was to receive a similarly grand welcome, but in terms of its significance, the London hockey victory would not get a worthy rival until the national hysteria that overtook India when Ajit Wadekar’s cricketers beat England in England in 1971. This was the true measure of what the hockey players had achieved a year after independence. The legacy of colonialism clearly mattered deeply, and the victory was one that will forever reverberate in the annals of Indian sport.