RevSportz Comment

One of the elementary mistakes you tend to be guilty of as a cub reporter is to make comparisons across eras and rush to snap judgements purely on the basis of numbers. For example, you could look at Chennai’s great off-spinner of yesteryear, Srinivas Venkataraghavan, and conclude that he was only half the bowler that Ravichandran Ashwin was because his strike-rate (95.3) was nearly twice that of the younger man (50.7).

Ashwin, as earnest a student of the game as any, would have been the first to laugh you out of the room if you made such a case. Better than most, Ashwin knew that he was carrying forward a torch that had been lit generations earlier, by several whose names are no longer even recalled.

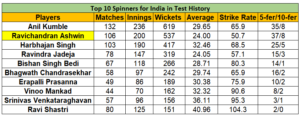

Across more than nine decades, only 14 Indian spinners have taken at least 100 wickets. Two of them – Anil Kumble, who sits atop the mountain with 619 wickets, and Ravi Shastri (151) – even coached Ashwin as he put record after record in the shade. But there are others, who didn’t even get to 100 wickets.

After independence, Ghulam Ahmed, the Hyderabad off-spinner, was part of India’s first great slow-bowling troika, alongside Vinoo Mankad and Subhash Gupte. He finished with 68 wickets in 22 Tests. Bapu Nadkarni, he of the relentless accuracy that would have shamed a Swiss watch, took 88 wickets in 41 appearances.

For the Latest Sports News: Click Here

When Kumble was in his prime, it was fashionable to compare his strike-rate with those of the legendary spin quartet of the 1960s and 1970s. Comparisons without context are nothing but daft. And the likes of Erapalli Prasanna and Bishan Singh Bedi would patiently explain to anyone who cares to listen how different cricket was then.

Theirs was a game of cat and mouse, with teams more than happy to score at a little over 2 runs an over. There was also the practice of pad play, with almost every batter tucking the bat behind pad while pretending to play a stroke. “How many do you think Chandra would have taken with his quicker ones if pad play wasn’t allowed?” was a constant refrain from both Bedi and Prasanna. For his part, Bhagwat Chandrasekhar would gush admiringly of how cleverly Bedi and Prasanna used flight and drift to draw batsmen into their traps.

Ashwin’s generation also had a bigger advantage that even Kumble didn’t have – the Decision Review System (DRS). For over a century, it was ingrained in the mind of every umpire that the benefit of doubt should go to the batsman. With the advent of DRS, such notions went out of the window. ‘Umpire’s call’ isn’t really about benefit of doubt for the batter, but more about factoring in possible errors in the technology used.

So, the numbers be damned. What we can, however, safely say is that Ashwin was a more than worthy heir of an incredible tradition. He loved his cat-and-mouse, especially against opponents like Steve Smith and Joe Root. Few things gave him greater pleasure than spotting a tiny chink and then exploiting it with impeccable execution of his plans.

India developing genuine pace-bowling depth over the course of his career also helped Ashwin. Where a Bedi or Prasanna had to take over a still-shiny ball from the likes of Abid Ali and Eknath Solkar, Ashwin often got to bowl to batters who had been softened up by the likes of Jasprit Bumrah, Ishant Sharma and Mohammed Shami. Even with the old, scuffed-up ball, they could be lethal, which meant the onus was never solely on him to win games.

Occasionally, it worked against him too. When you play an overseas Test as the lone spinner, the expectation is so much higher. In some ways, Ashwin’s card was forever marked by his failure to bowl India to victory on the final day at the Wanderers in 2013. He wasn’t the only one thwarted by AB de Villiers and Faf du Plessis that day, but he was the scapegoat.

While he didn’t miss a single home Test after his debut, Ashwin played only 41 of the 67 Tests that India played away during his career. On occasion, the selection calls were positively bizarre – like Karn Sharma being chosen ahead of him in Adelaide in 2014. If those omissions stung, he never showed it out on the field, where he was the consummate team man with ball or bat.

When Ashwin made his debut, back in November 2011, Indian cricket had an end-of-era feel to it. It’s there again now, with Ashwin joining the likes of Cheteshwar Pujara, Ajinkya Rahane and Ishant on the sidelines. Others will follow sooner rather than later. But as he walks away, Ashwin can look back and say with absolutely certainty that he leaves Indian cricket in a better place.

Also Read: Ravichandran Ashwin – celebrating a maverick thinker who always speaks his mind