By Anindya Datta

It is the early 1950’s. A young girl, Kiran, spends hours playing with her siblings on a small dusty plot of land adjoining their house. They are happy times filled with the innocence of childhood. A sign on the wall, Jallianwala Bagh, holds no special significance for the sisters.

The enclosed area doesn’t look much like a garden. It never has. Not even three decades before, when the innocuous looking Quadrangular gained notoriety literally overnight.

Rewind to March 1919. The Rowlatt Acts have been passed. Indians are subject to imprisonment without cause, trial without a jury, and a range of punishments expressly designed to humiliate. Gandhi calls for a general strike in protest, and the British react by arresting prominent leaders.

Among other cities, Amritsar erupts in protest. Parts of the city, particularly the narrow lanes that lead up to the Bagh and the Golden Temple beyond, are not fully under British control. Anticipating problems around the Baisakhi holiday, a ban on public gatherings is announced. But few within the city, and almost none outside it, receive the message. Thousands of Punjabis converge in the heart of Amritsar to celebrate the occasion.

On the 13th of April 1919, as a few thousand people congregate at Jallianwala Bagh to celebrate the festival, Brigadier General Dyer, tasked with maintaining peace in the city, marches into the Bagh. He is leading fifty soldiers armed with .303 Lee–Enfield bolt-action rifles. It is part of the troops moved the previous day from regimental headquarters in nearby Jalandhar. He leaves two armoured cars just outside the entrance.

Jallianwalla Bagh is, at the time, a private property whose main entrance is a narrow passage that can barely accommodate three people (it is the only reason the armoured cars remain outside). It has four other very small exit points. Dyer seals off the other exits, and leads his troops in. Then, without any warning, he orders the soldiers to open fire on the crowd until all their ammunition is spent. He specifically asks them to shoot to kill and pick off those attempting to escape over the high walls of the enclosure and through the doorways. 1650 rounds of ammunition are exhausted in the ten minutes of carnage.

Dyer then orders his men to leave the Bagh. No help is given to the wounded despite the fact there is a curfew he has himself declared in the city. Between 379 to 1,000 men, women and children die from the indiscriminate firing and lack of medical care thereafter.

Barely an hour after the massacre, blissfully unaware of what has transpired, Sydney Montague Jacob, ICS, born in Dalhousie, a man deeply sympathetic to Indians, and then Director of Agriculture in Amritsar, drops into Commissioner Miles Irving’s office, to pay a courtesy call before leaving on a tour of the districts.

While he is there, Irving receives a call from Brigadier General Dyer’s headquarters where they hear for the first time about what has happened. Dyer confirms that he has already wired lieutenant governor of the Punjab, Sir Michael O’Dwyer, on whose instructions he had brought his troops to Amritsar. He also confirms that O’Dwyer has fully endorsed his actions. And adds, for good measure, that if he could have taken his armoured cars inside, and continued firing for longer, he would have done so with pleasure.

The conversation shocks and incenses Jacob. Notwithstanding what Dyer has said about informing O’Dwyer, Jacob insists that Irving write out a full independent report leaving nothing out from Dyer’s account. He eventually prevails over both Dyer’s and Irving’s opposition and drives to Lahore to deliver the report, with a Sikh friend, Wathen, the principal of the Khalsa College.

Jacob and Wathen arrive at 3 a.m. and wake up Sir Michael, who reads the report and responds frostily to their comments. Nonetheless, O’Dwyer is forced to acknowledge the report, which then goes into the official files on the incident. Eventually it becomes one of key documents that is responsible for the action the British parliament takes against Brigadier Dyer in depriving him of his government pension.

Dyer is censured and removed from service after he returns to England, and British troops are forbidden from firing on civilians henceforth. Three decades later when partition riots erupt across the country, using this as a precedent, British troops stand by with the Jallianwala Bagh sword hanging over their necks, their guns silenced.

Back in Amritsar, the British government imposes a news blackout on the incident. For months, the details of Jallianwalla Bagh are suppressed. When news starts filtering out, the only public figure who reacts immediately is Rabindranath Tagore, returning his knighthood in protest. Gandhi will not act for another year, in a misguided hope for redemption and apology.

But the first man within the system to lodge his protest is none other than Sydney Jacob. Immediately after the incident, he resigns in protest at the massacre, is shunted out of the limelight and appointed Superintendent of Census Operations.

This suits Jacob fine. The 1921 Census of India is being conducted, and he immerses himself in this task. Jacob goes on to co-author the report that forms the core of the census report on Punjab and Delhi, two of the most important areas included in the survey.

The time that his involvement with Census Operations affords, has a far reaching if unexpected impact on Indian tennis. Free to indulge his passion for the sport in which he has for years been recognised as a rare talent, Jacob begins to take part in, and regularly wins tournaments in India and Europe.

In 1921 he plays Wimbledon for the first time, reaching the fourth round. That year, alongside the nation’s best tennis players of the time, Mohammed Sleem, Lewis Deane, and the brothers – Hassan Ali and Athar Ali Fyzee, Jacob turns out as a part of India’s first Davis Cup team, and in a stunning turn of events, defeat world champions France. They march into the semi-finals, only to lose to Japan in the unfamiliar freezing conditions of America.

In 1923 Jacob once again reaches the fourth round at Wimbledon. That year he also captains the Davis Cup team to a quarter final slot and in 1924 reaches the quarter-finals of the Paris Olympics.

In 1925, at the age of forty-five, Jacob is invited to play at Roland Garros at the French Championships. For good measure, he is seeded eighth. In the third round, Jacob gets past Jacques Brugnon in four captivating sets of tennis. He then defeats Andre Gobert, a former Olympic silver medalist and Wimbledon finalist, once again in four sets. In doing so, he becomes the first Indian to reach the semi-finals of a Grand Slam. It will be another three decades before Ramanathan Krishnan repeats the feat.

In the semi-finals, Jacob runs into the second of the Four Musketeers, Rene Lacoste. While Lacoste may be better known today for the brand with the ‘crocodile’ logo founded by him and his partner Andre Gillier in 1933, in the mid-1920s it is Lacoste’s tennis that is all the rage of the tennis world.

Jacob and Lacoste battle it out on the Roland Garros’ clay for over three hours before Lacoste prevails in four hard-fought sets, 6-2, 6-1, 4-6, 7-5. In the finals, Lacoste beats Jean Borotra in straight sets to win the first of his ten Grand Slam titles. For Jacob, the semi-final appearance marks the peak of a remarkable tennis career.

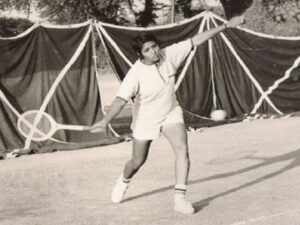

Sydney Jacob, ICS, is however not the only Indian tennis player with a close association with Jallianwalla Bagh and the events that unfolded this day over a hundred years ago. The little girl whose innocent feet raced over the grass three decades later follows in his footsteps in more ways than one. Little Kiran goes on to win both the National and Asian Tennis Championships.

Off court, the similarities with Jacob’s personality are uncanny.

Kiran’s fight against injustice starts as a teenaged tennis player. She lodges a public protest against the Punjab Lawn Tennis Association for pay discrimination against female players. From there, her intolerance for the unjust, moves to the next level.

She takes upon her young shoulders the mantle of a broader fight for law and justice in India. Passing the All-India Civil Services Examination with flying colours, Kiran Bedi becomes India’s first female IPS officer.

In an interview as a trainee, she says, ‘Policing, for me, is about the power to reform, power to provide instant justice. This is my mission.’

Over a stellar policing career Bedi becomes IG of Delhi Prisons, reforming Tihar Jail at the time, wins the Ramon Magsaysay award. She is also the first Indian woman to be appointed as a police advisor to the secretary-general of the United Nations.

As we remember the hundreds of innocents who lost their lives on this day, it is perhaps poetic justice that we also celebrate the achievements of two Indians with close links to the Bagh – Sydney Jacob and Kiran Bedi, two of India’s tennis greats who led the fight against injustice while bringing sporting glory to their nation on other, less fatal patches of red soil around the world.