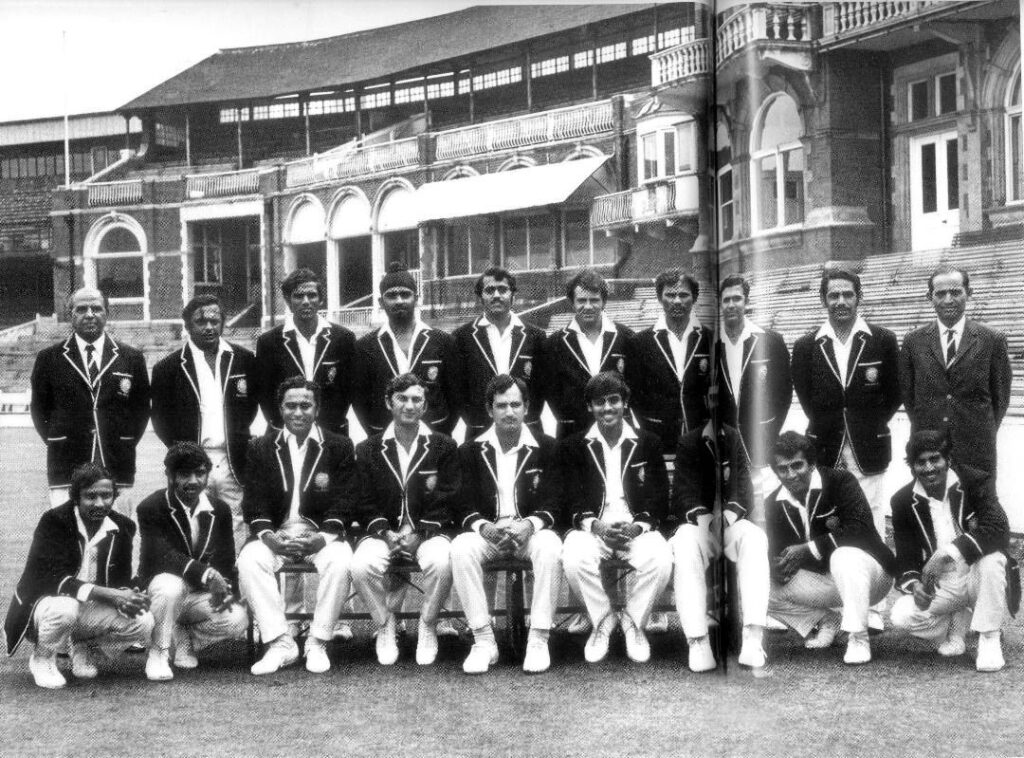

India’s win at The Oval in 1971 was a miracle. Much like the 2001 victory against Australia at the Eden Gardens, where India won after following on, they came from behind at The Oval to hand England their first series loss in years. While the victory will forever be cited and analysed as a spectacular underdog-success story which marked the initiation of a new order in world cricket, it should also be remembered that India had played well right through the series and had stepped out at The Oval with reputation enhanced. The victory was vindication of a playing philosophy first seen in the West Indies earlier that year, and it gave a serious shot in the arm to the Ajit Wadekar-Vijay Merchant pairing.

While Wadekar was now the undisputed leader, Merchant could hang up his boots as Chairman of the Selection Committee later in the year, leaving behind a legacy that would be difficult to replicate. While the victory has been much talked about, there are tales subsumed within the bigger story of success that illuminate that Oval win as one of the greatest moments in the history of Indian cricket.

The star was undoubtedly Bhagwat Chandrasekhar, who ran through the English second innings in just two and a half hours, setting up what was one of the most important chases in Indian cricket history. And in doing so, Chandrasekhar successfully proved a point. Dropped for the West Indies tour and picked on by the Chairman of selectors ahead of the England series, it was a special effort from one of India’s greatest, and utterly unorthodox, leg-spinners. This effort, to many of his colleagues like Sunil Gavaskar, Gundappa Viswanath and, of course, Wadekar, his captain, was the best Chandrasekar had ever bowled.

It was fitting that he did so in what was the most important Test match of his career. While he did not say much about Merchant’s jibe ahead of the team’s departure for England, except to note that the Chairman should not have picked him if he did not have faith in his abilities, there is little doubt that it was playing on his mind. While Chandra was less vocal on the issue, that he had a point to prove after being overlooked for close to two years is beyond doubt.

He had fought his way back into the team with strong domestic displays, and was a top performer in England all through the series. What was missing was that one miracle effort. There could be no better stage than The Oval, with England in the driver’s seat and seeking to take control of the game. They had scored 24 for the loss of John Jameson, a run-out call which went India’s way when Chandra deflected a Brian Luckhurst drive on to the wicket. England, at that point, had an overall lead of 94 runs, substantial in the context of a low-scoring game. India, by every estimate, was praying for a miracle. And India, by every estimate, did get one.

Chandrasekhar at the Oval

While I have spoken to Chandrasekhar at length, stories which are documented elsewhere, what I want to do here on his birthday is to highlight the importance of this spell for India and for Chandrasekhar himself. Chandrasekhar, as many of his colleagues that I have spoken to suggested, needed a little time to settle into his rhythm. He took three or four overs to get into groove, and after that started to have a telling impact on the game. India did not have the time at The Oval, with England starting to dictate terms.

Each run added to the score was going to make the run chase that much more difficult. With lunch round the corner, it was a critical moment in the game. Had England played out the last few minutes before the interval without losing a wicket, it could have meant that the game was beyond India. They would have time to recalibrate and with a lead of close to 100 in the bank, they could easily start to control the game going forward.

Did any of this play on Chandra’s mind as he stepped up to bowl to John Edrich? Did he think he had to pick up a couple of wickets in his very first over to dent England? Do performers think like this? Did he dream of doing a Salim Durrani at The Oval to change the complexion of the game in a matter of minutes?

In the absence of great television coverage, all we have is Edrich facing up to Chandra with his back to the camera. And while it is not a close-up shot, what we do see is Chandra running in from over the wicket. Within a flash, Edrich’s stumps are shattered. It all seems very sudden. Edrich turning back not really knowing what had happened, Chandra trying to come to terms with what he had done, and the close-in fielders waking up to something unexpected. The story goes that as Chandra ran into bowl, Dilip Sardesai from his fielding position screamed “Mill Reef”, and Chandra, midway through his run-up, changed his grip and bowled a faster delivery, something he has spoken about in many interviews over the years. Both Chandra and Sardesai were fond of racing, and bet on horses right through the summer. Mill Reef, the Epsom Derby winner that year, was one of the horses they had bet on, and Sardesai screaming the horse’s name was a signal for Chandra to bowl a quicker ball.

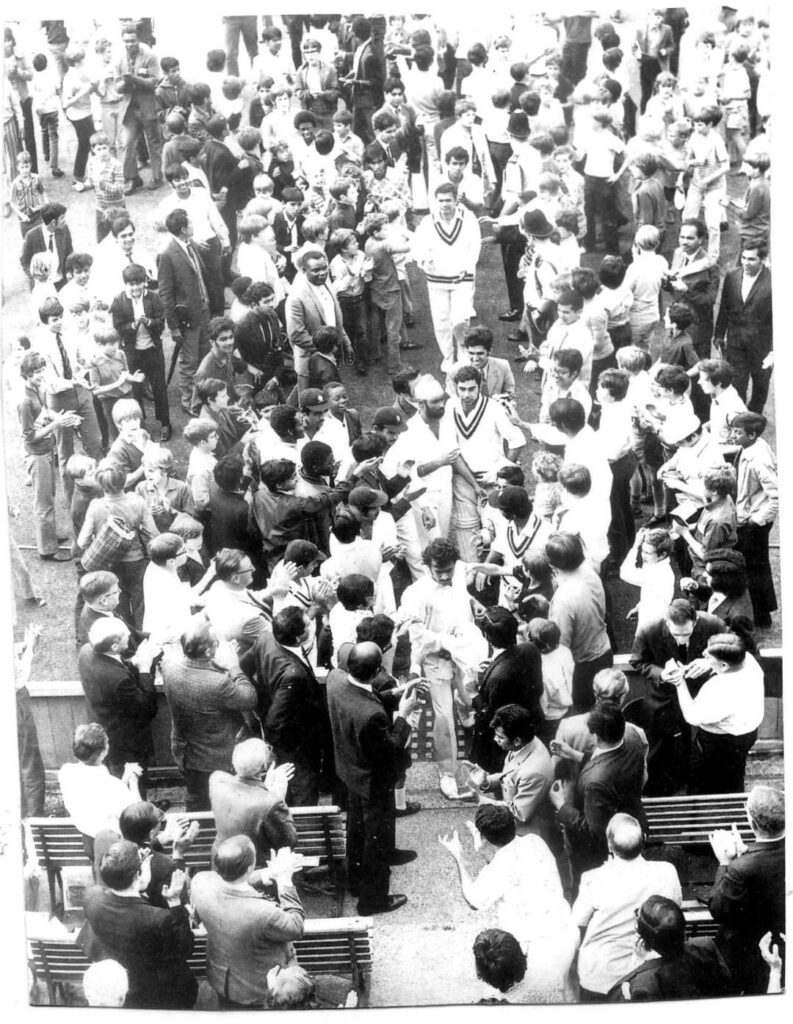

The celebrations, however, were muted for the Indians couldn’t gauge what was to follow. Chandra too went about his celebrations in a rather routine manner. It was as if he were practicing social distancing in post-Corona times. No hugs or high fives, and all he did was walk up to the wicket-keeper as Bishan Singh Bedi ran in to congratulate him. Things were dramatically different at the fall of the next wicket. With lunch round the corner, Wadekar had Fletcher surrounded by five fielders close to the bat and India were on the prowl.

And just as Fletcher edged to Eknath Solkar, who was brilliant at forward short leg, Chandra jumped up much like Cristiano Ronaldo in what was an unexpected burst of energy. Chandra was in business, and so were India. In the words of Captain Wadekar, “The match was irrevocably settled by mid-afternoon. At Port of Spain, Durrani had claimed Sobers and Lloyd to put us on the road to victory. At the Oval, the moment Chandrasekhar bowled Edrich and Fletcher, off successive balls, I sensed that the game would be ours. Chandrasekhar’s length, the crippling influence he exercised over the English batting was such that I could well dispense with our other star spinner. While Chandra ran amuck at one end, I brought Venkat on to keep runs down at the other….England were hounded to their doom, as Solkar, in the close-in position, lent an added edge to the attack. It was one long procession as England’s batsmen were unable to tell Chandra’s top spinner from his legbreak…Chandra’s figures of 18.1-3-38-6 deserved to be engraved in letters of gold. By destroying England’s batting he had raised hopes of victory.”

Speaking of this spell, Viswanath was more fan than colleague. While repeating multiple times that the spell at the Oval was the best he had seen Chandra bowl, he dismissed the myth that Chandra did not know what he was doing. According to Vishwanath, there is no such thing as a mystery bowler. If a batsman is unable to pick the ball from the bowler’s hand, it remains a mystery to him. From standing at slip, he could understand everything that Chandra was trying to do, and says that from ball one, everything about the spell was perfect.

“It was a special day,” said Viswanath. “Rhythm, pace, variation, everything seemed perfect. We often use the term unplayable rather loosely. This was one spell that was truly unplayable.”

While most journalists covering the game hailed Chandra as the best in the world, for Wadekar and the team, he had opened up the game. From 71 behind in the first innings and staring at a 300-plus run chase, India were left with a target of 174 to beat England in England for the first time. At stake was not simply a Test win, but a series triumph that could take Indian cricket to a height never achieved before. It was India’s moment of reckoning, set up beautifully by Chandra.