— Souvik Naha

Atul Mukherji, the editor of the Khelar Asar, was a first division cricketer when West Indies came to play a Test series in 1948–49. Equipped with 20 rupees given by his maternal aunt, he went to CAB Secretary Amarendranath Ghosh’s (A. N. Ghosh) house at Mango Lane in central Calcutta where Ghosh personally sold tickets. The ticket covered both the Test and the match against the Governor’s XI. Mukherji bought one. He was told before leaving, ‘come back should you need more tickets’.58 Twenty years later, during the India–Australia Test match in 1969, around 20,000 people queued before daybreak for the 7,000 day-tickets on sale, leading to a stampede, six deaths, infamy for the city’s cricket administrators and end of the practice of selling day-tickets until 1993. The press mourned the deceased and expressed shock about the public’s morality considering that the tragedy was quickly forgotten and the match continued without any homage to the departed. What was it about cricket that made the people of Calcutta scamper for ticket, giving new meanings to the Eden Gardens as a space and writing a new handbook of collective behaviour?

In terms of the quality and breadth of content, the late 1950s represent a watershed for media attention to cricket, in which Rohan Kanhai’s innings of 256 runs in a single day in 1958–59 can be claimed to have been a turning point. As international cricket piqued people’s interest in attending matches, the press began pondering, sometimes amplifying, what cricket meant to them. The pot started simmering when Pakistan played in Calcutta in 1960–61. It was the first time newspapers reported people clashing with the police and queueing for tickets. The pot came to a full boil as India faced England in 1961–62. Ticket distribution was now politicised so much that the editor of the Anandabazar Patrika compared the method of acquiring match tickets with the dismal culture of people using influential patrons, usually politicians, to ensure success in school admission, government job or hospital admittance. Cartoons reflected the desperation of watching the match by showing, for example, a person asking an acquaintance, who was carrying a large holdall, if he was travelling out of Calcutta. The second person responded that he was going to queue outside the Eden Gardens. Another cartoon showed two cold passers-by enjoying the heat generated by a scuffle for tickets. In a third cartoon, a trader sold tickets for seats on the branches of a tree next to the ground, implying the stadium was sold out. Journalist Santosh Kumar Ghosh wrote satirically that police constables left no stone unturned to be assigned duty at the stadium.

In 1964, to give more people the chance to watch cricket, the CAB reduced the number of season tickets and released daily tickets, 6,000 priced at 5 rupees and another 1,200 at 10 rupees. Massive queues formed in front of the ticket counters every morning. People started to queue up to 30 hours in advance to buy the first day’s ticket; the first in line was a student from Bengal Engineering College. Fifty black marketeers were arrested even before the match began. As the police baton-charged the thousands assembled to see foreign cricketers practise, the people pelted stones. The press reported double-booked seats, overcrowded galleries, and brawls with fellow spectators and the police. The situation became so outrageous by the third day that spectators set fire to the canopy 10 minutes before the end of the day’s play. The Dainik Basumati editorialised that the incident was not an abrupt outburst, but ‘written on the wall’. The police force in 1964 was neither properly trained nor numerically strong to control crowd disturbance. According to a satirical report in the Anandabazar Patrika, in the second tier of the gallery, a spectator so fiercely and skilfully spun a stick in a circular motion that the police did not dare to get close and apprehend him. Ten young men hurled earthen teacups at constables, which must have been an inexhaustible barrage considering around 10,000 people bought tea at the stadium that day. The police arrested a number of spectators, claiming that throwing cups was illegal. The first aid personnel were happy to have become useful. As two injured spectators were carried out on stretchers, someone who presumably was never ferried on a stretcher before chased one as if running after a rush-hour bus.

The press was unequivocally supportive of spectators despite their poor behaviour and critical of the police and the administration, who were unprepared to handle crowd pressure. The sports journalist Santipriya Bandopadhyay wrote that after all the trouble of acquiring tickets, the public did not deserve to find their seats occupied by others bearing the same ticket, with no way to know whose ticket was counterfeit. Readers were not so forgiving, as is evident from the letter Nabakumar Shil wrote to the Jugantar about how sections of spectators ‘heroically’ fought with sticks, set fire to the awning and pelted one another with fruit skins and teacups. He deplored how unsporting the spectators were, having little inclination to abide by the dedication and discipline of cricket and cricketers. The public earned no right to call themselves sports lovers simply by watching cricket in droves or displaying elite tastes and knowledge; their behaviour should be worthy of being ranked alongside that of cricketers. With little compulsion of supporting the fledgling run of international sports in the city, readers were primed to show more chagrin than journalists.

West Indies postponed its 1964–65 tour as India went to war with Pakistan. They visited Calcutta in 1966–67 amidst high expectations. Watching the enthusiasm with which West Indian cricketers were greeted once out of the aeroplane, author Narayan Gangopadhyay was certain that in his next birth, he wanted to be a cricketer and not a politician, an author, a singer or an actor as they did not come close to the unreserved adulation for cricketers. The riot on 1 January 1967 led many people to blame newspapers and radio for fomenting cricket frenzy in the state. In self-defence, journalists said that the problems in organised sport reflected a pervasive social malaise, which could be possibly redeemed by indulging the philosophy of cricket. The author Chanakya wrote in the Desh that cricket was a real art, and the public should plunge into cricket instead of setting busses on fire. With India’s decline in international football, cricket and hockey were the only alternatives to claim a foothold in world sports. The public must have seen something great in cricket as sheer craze would not have made thousands queue for tickets for hours year after year. People without ticket, instead of returning home in despair, often convened outside the Eden Gardens and listened to radio and the occasional cries of jubilation coming out of the ground. Although the riot tarnished Calcutta’s image and the press was critical of the lumpenisation of spectatorship, the public were in no mood to be discouraged. The rising need for tickets substantiated the theory of scarcity driving up consumption. Women were frequently accused of blocking seats of male cricket lovers. Well-connected and financially solvent upper-middle class women, who could afford the high price, went to the stadium in droves. People without tickets earnestly read match reports and consumed the cynical portrayal of these women whose presence was suspected to have made tickets scarce, depriving them of the tactile enjoyment of cricket.

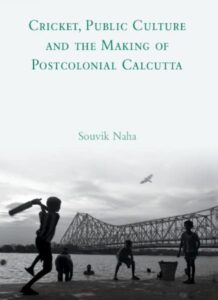

Souvik Naha, Cricket, Public Culture and the Making of Postcolonial Calcutta (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).