Just days before Sachin: A Billion Dreams was all set to hit movie screens around the world, someone asked me what a film on Sachin would have to offer. His life was an open book and people had followed him since he was a child – that was the crux of the argument. To be fair, it was a very pertinent comment. Sachin Tendulkar is one of the most-talked-about personalities in the history of modern India, and what would a biopic of his offer us that we did not already know?

First things first – biopics or documentary dramas help expand the constituency. In an age when people consume things visually on smart phones and when reading habits are on the wane, it is essential that films or biopics step in to fill a void. For an eight year old growing up in a “smart” India, a dramatised visual representation is perhaps the most powerful means to perpetuate a legacy, far more significant than the videos on YouTube or the written word.

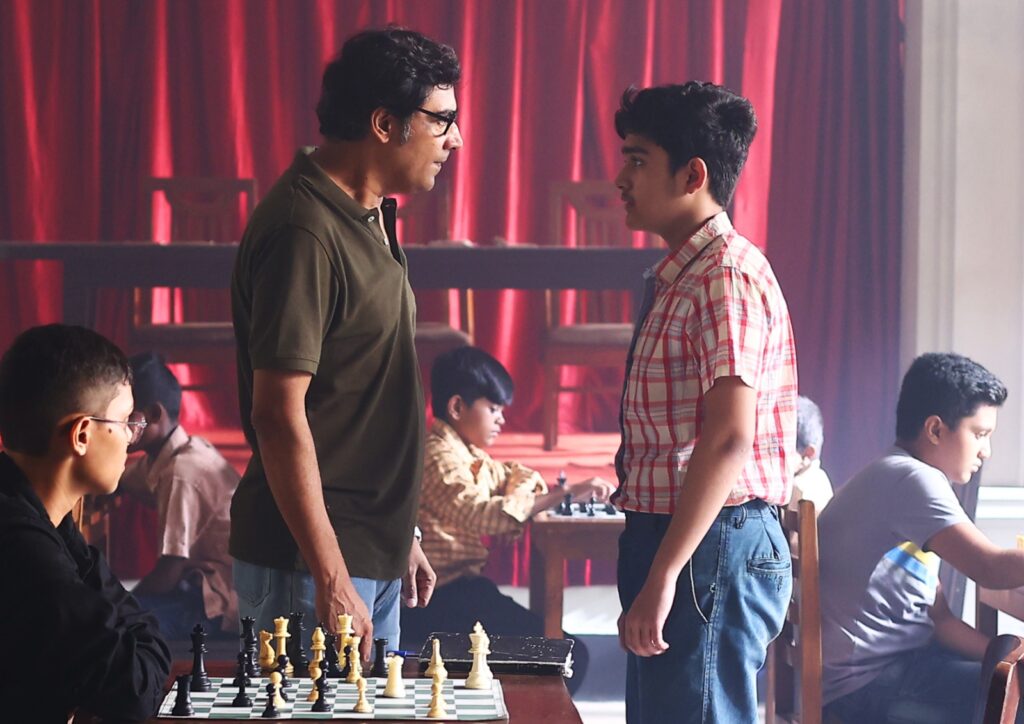

And sport is also about timing. Chess in India is at an all-time high with D Gukesh winning the Candidates. Praggnanandhaa, Gukesh, Vaishali, Vidit – the new crop of Indian chess is doing incredibly well and the sport is getting serious corporate support for a change. That’s what makes Dabaru a very timely film. Inspired by the life of Surya Sekhar Ganguly, the film documents his rise from a very humble background to becoming Grandmaster – a title that seemed a million moons away to him and his family.

Dabaru isn’t an aberration. Rather, one of the good things to happen to Indian sports in recent times is the immortalisation of some of the success stories in the form of biopics and period films. A trend that started in earnest with Chak De! India was carried forward by Paan Singh Tomar, Bhaag Milkha Bhaag, Mary Kom and, more recently, 83 and Maidaan, which celebrated the 1983 World Cup win and the 1962 Asian Games football gold-medal triumph.

Entwining a tale about nationalism with a narrative concerning the neglected state of Indian chess, which lacked funding in the early 1990s, Dabaru has brought a known story of indifference and discrimination to light. It helped illuminate how chess remains trapped within traditional stereotypes – often compared with cards and gambling. The film used a conventional framework to accommodate markers like cultural values, issues of identity and the ultimate sporting dream of winning the title of Grandmaster.

May I say, I love watching sports films. Not simply because they speak about epochal events or icons in sport, but also because they help understand the true meaning of sport in Indian life. These films use the prism of sport to know India better, and in doing so, give a new lease of life to Indian sport. Sport isn’t just a news bulletin of 30 minutes. It is not a silo to be submerged by politics. It is a defining marker of Indian identity, and that’s what sports films have at their core.

At a time when Indian sport is breaking new ground, these films help us take pride in Indianness and that’s no mean achievement. Frankly, that’s what unites all the sports films, and Dabaru is yet another valuable addition to this growing repertoire. Seeing sports films get the support they deserve makes me optimistic that there will be more made in the coming months and years. Wish Dabaru all success, and anyone who fancies the sport should certainly go and watch it.