George Lois and Carl Fischer. If you mention these names to the average sports fan, there is unlikely to be a nod of recognition. But their most famous work, an Esquire magazine cover from April 1968, is one of the iconic images of the 20th century. Forty years after it was published, The Associated Press wrote: “The photo is so powerful that some people of a certain age remember where they were when they saw it for the first time.”

Lois, the magazine’s art director, and Fischer, the photographer, had Ali pose as Saint Sebastian, with six arrows embedded in his body. The picture symbolised how Ali, the greatest boxer of his day and a rallying point for people of colour across the world, had been victimised for his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War.

The magazine hit the newsstands on April 4, 1968, the same day that Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. King had led the Civil Rights Movement that attempted to reform a deeply racist and segregated society, and his murder further increased tensions.

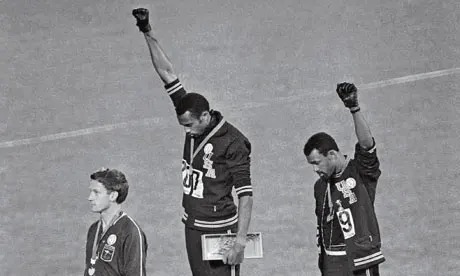

The Esquire cover stands as a monument to those troubled times. Later that year, there would be an equally famous photograph taken, at the Olympic Games in Mexico City. After Tommie Smith and John Carlos had won gold and bronze in the men’s 200m, they took to the podium wearing black gloves. The right one on Smith’s hand, and the left worn by Carlos. Both fists raised to the sky, and heads bowed to symbolise the Black Power Salute.

Both would be blacklisted by the American athletics fraternity, but their gesture will never be forgotten. Peter Norman, the Australian silver medallist, also joined in the protest by wearing a badge, recognising that it went beyond race and politics and was about basic humanity.

Before the start of the 2016 National Football League (NFL), Colin Kaepernick, the San Francisco 49ers quarterback who had led them to a Super Bowl – American Football’s showpiece – sat during the playing of the national anthem before a pre-season game, in protest at what he perceived as police brutality against people of colour. “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” he said afterwards. “To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

During the season, Kaepernick would kneel during the playing of the anthem. Pilloried by sections of society and the media – almost all, coincidentally, a certain skin colour – he hasn’t played in the league since. Those without even a smidgen of his talent continue to get multi-million-dollar contracts. Kaepernick hasn’t taken a single snap, and is now an activist for the cause that cost him his career.

Each of these images is unforgettable. Not just because of their stark quality but because of the power of the messages. Maybe the common man could relate more because these were men and women who had spent years training in spartan conditions to reach the pinnacle of their sports. And they were then prepared to sacrifice glory for the sake of something bigger.

All those pictures came to mind when you saw images of Vinesh Phogat and other wrestlers lying on the ground in front of Jantar Mantar, while law-enforcement officials tried to drag them into the back of police vans. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the situation, those images will not be forgotten by those that saw them. They will become India’s equivalent of the Black Power Salute, and Taking the Knee.

One doesn’t usually associate athletes with political protest. In fact, the likes of Sachin Tendulkar and Virat Kohli have frequently been criticised for not taking a stand on the issues of the day. This is not apathy. Most of the time, sportspersons stay away from subjects where they feel they don’t have an informed opinion to offer. And there is nothing wrong with that.

But when an Ali – “no Vietcong ever called me n***er” – or someone of that stature makes a political statement, it touches even those who otherwise ignore the front pages of newspapers. An Ali or a Vinesh aren’t just athletes, they are powerful symbols of change. If one became the symbol of change in a deeply divided America, the other is one of the faces of women’s emancipation in India. Any image that portrays them as victims is therefore exponentially more powerful.

Even those born decades after the Black Power Salute have seen the picture. Journalism and design students still study that Esquire cover. And as much as some might want to airbrush it away, that image of Vinesh on the ground, face contorted in pain, will also endure. It won’t be forgotten.

Also Read: Violence Cannot be the Solution for Wrestlers’ Protest