Rohan Chowdhury, Oxford

The streets feel like history, the breeze smells of books — Oxford isn’t just a city, it’s a time capsule. Step out of the Oxford railway station, take a few turns toward the city centre, and the place begins to speak. Not in words, but in atmosphere. Every corner has a story to tell.

Who doesn’t know about the University of Oxford? A university that, over more than a thousand years, evolved in its own unique way. Now an amalgamation of 43 colleges, it stands as the oldest English-speaking university in the world, with records of teaching dating back to 1096.

Visiting the Oxford University Cricket Club felt like stepping into a living history book. The wooden pavilion and dressing room seemed older than time itself, yet stood sturdy and familiar — like a relic respectfully cared for. It was heritage, not just preserved, but alive.

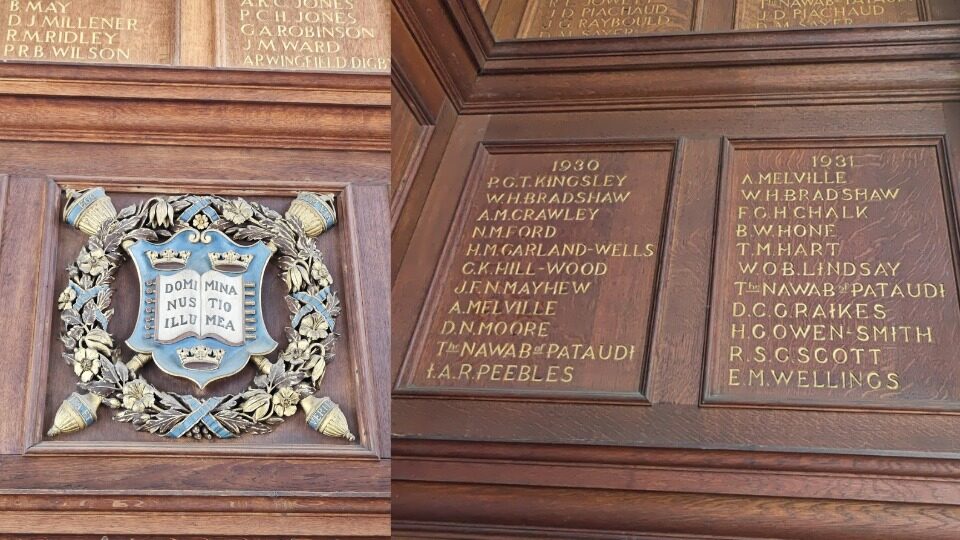

The walls of the Long Room — part conference hall, part dressing room — were lined with wooden plaques, chronicling the names of team members year after year since the club’s inception. A brilliant archive, carved into wood with the precision of tradition and the pride of continuity.

From M.R. Jardine to the Nawabs of Pataudi to Imran Khan, the walls spoke volumes. One of the first plaques that caught the eye was from 1891 — the name etched into history: M.R. Jardine. Malcolm Robert Jardine, an English first-class cricketer from the late 1800s, played primarily for Oxford University.

According to Wisden, in 1892, during his final match for the University, Jardine repeatedly played an unorthodox shot — glancing Stanley Jackson, the Honourable Stanley Jackson, down the leg side. It was a stroke not common in that era. Interestingly, a young Colonel Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji II — better known as Ranji — was present at Lord’s that day. Ranji would later make that shot famous as the “leg glance.” But it was Jardine who, perhaps unknowingly, pioneered it.

Malcolm’s legacy extended through his son, Douglas Jardine — a name that evokes as much reverence as it does controversy in English cricket. A former Oxford player himself, Douglas captained England from 1931 to 1934 and masterminded the infamous Bodyline strategy during the 1932–33 Ashes against Australia. The plan: bowlers targeting the batter’s body with short deliveries down the leg side, particularly aimed at Don Bradman. It won England the series 4-1, but at a moral cost. Jardine bore the brunt of both criticism and admiration, cementing his place in cricketing folklore.

The walls of the Long Room echo those stories without saying much — just names, dates, and wood, but the silence is rich with legacy.

Among those names, “Pataudi” appears more than once. Iftikhar Ali Khan Pataudi featured in the 1929, 1930, and 1931 plaques. He was a part of the Bodyline tour but famously objected to the tactic and was dropped from the third Test. His quiet dissent became part of cricket’s moral dialogue.

Three decades later, his son, Mansoor Ali Khan ‘Tiger’ Pataudi, followed in his footsteps. The 1960 plaque marks his time at Balliol College. A separate metal plate on the wall honours him further:

“In celebration of the timeless achievements of M.A.K. ‘Tiger’ Pataudi (1941–2011), Oxford University CC, Sussex and India.”

Later, he would go on to captain India, redefining its cricketing spirit — all with one good eye.

Another name that stands out — C.B. Fry. Charles Burgess Fry wasn’t just a cricketer; he was a phenomenon. He captained the Oxford University Cricket Club in 1894, and England in 1912. Fry also played football for England, reached the FA Cup final with Southampton, and in athletics, broke the English long jump record — equalling the then world record. A man of mythic proportions, Fry’s plaque radiates charisma that seems to transcend time.

Moving away from the wooden memorials, one of the most unique objects in the University Parks is a quiet white bench. To the casual observer, it’s just a place to sit and enjoy a county game. But look closely — a small stainless-steel plaque on the backrest reads: “Dr Tony Lewis M.B.E., Co-Founder of the D/L Method. Who enjoyed watching cricket here.”

Yes, that Lewis — of the Duckworth-Lewis method. A complex system that few understand, but all know. Dr Lewis, a lecturer at Oxford, often watched matches here. His wife had the plate installed three years ago and has requested a larger tribute be placed elsewhere in honour of his contribution to the game — and his quiet love for the club.

Not far from there stands another bench, named after Lord Colin Cowdrey of Tonbridge — former OUCC and England captain. “Remembered by his Oxford friends,” reads the plaque. A middle-aged local, seated nearby, chuckled and said, “He came here, but couldn’t finish his PhD because he played too much cricket.”

Then he added, with a laugh, “He just played and played and played.”

As I left the Long Room, the groundsmen were at work, preparing the pitch for the final match of the series. At the moment, it was a dense green top — but in three days, it would be ready.

The visit to University Parks was more than a journey through a cricket ground. It was a walk through history — a perfect blend of heritage and modernity. It reminded me that preserving roots isn’t just about nostalgia. It’s about respect — and recognising the legacy that shapes the present.