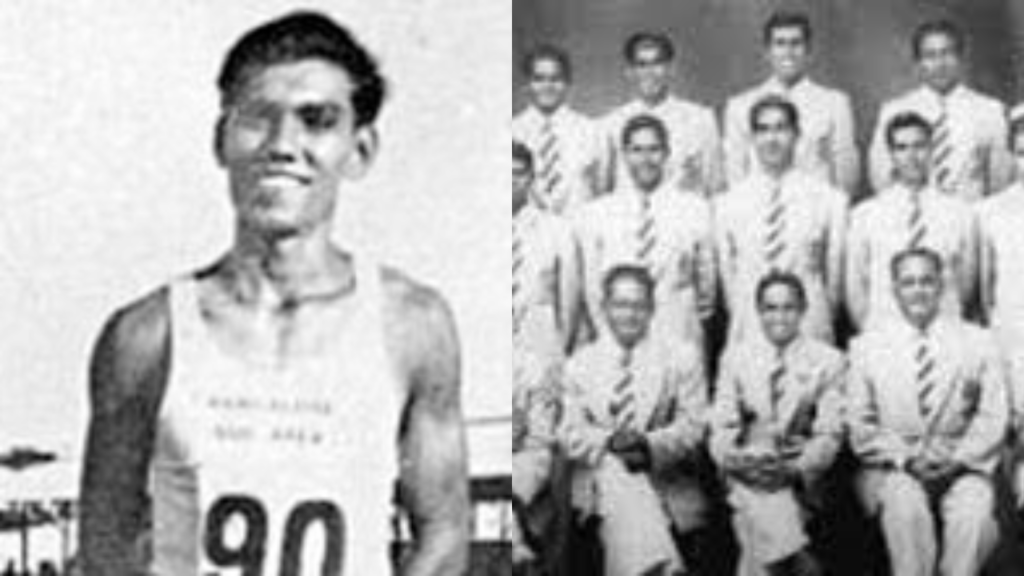

When we speak of heartbreaks at the Olympic Games, the first Indian name that comes to mind is that of Henry Rebello. He was distinctly unlucky in the London Games of 1948. A 19-year-old triple jumper, Rebello was a favourite to clinch gold, having shown exemplary promise in meets preceding the Games and consistently jumping over 50 feet, the distance covered by the eventual gold-medal winner in London.

Highly rated by experts, Rebello had qualified for the finals with ease – a jump of 49 feet, easily clearing the cut-off of 48 feet, 6 inches. But as luck would have it, he tore a muscle during his first jump in the final and had to be carried off the field in pain in one of the worst tragedies in India’s athletic history.

This is how he later described his fate. “We were huddled in our tracksuits and under blankets to keep ourselves warm,” he said. “I was training with Ruhi Sarialp of Turkey when it was time for my turn. I was wondering how to approach the event. Should I go for a big jump in my first effort, or keep it till the third or fourth attempt? I took off the track suit and was getting ready when an official suddenly stopped me as a prize distribution ceremony was about to commence near the jumping pit.”

When he was asked to commence his jump 15 minutes later, Rebello committed two follies that transformed his life. “I was just 19-and-a-half and inexperienced,” he would say later. “I should have insisted on some time for warming up. That was my first mistake—not to warm up. My second was to go flat out on my first jump. We had a total of six and I should have taken things easy at the start…

2016 Rio Olympics and the tennis heartbreak!#SaniaMirza and #RohanBopanna nearly secured India’s second Olympic tennis medal but lost the bronze playoff.

The story of So Near Yet So Far by @BoriaMajumdar.@FederalBankLtd @rohanbopanna @MirzaSania @WeAreTeamIndia #Olympics pic.twitter.com/hlhQ9nCySz

— RevSportz Global (@RevSportzGlobal) July 21, 2024

“I approached the take-off board at considerable speed. I got my take-off foot on the board and started to take off for the first phase of the triple jump—the hop. Then, suddenly, I felt a sharp pain in my right hamstring muscle and heard a sort of ‘thwack’ like the snapping of a bowstring. My right hamstring muscle had ruptured. I was thrown off balance completely and landed with a tumble in the pit.”

Rebello, as Gulu Ezekiel has written, ‘was carried off a on stretcher in agony. His hopes and dreams had been crushed.’ Sarialp, who Rebello had out-qualified by nearly five inches, would go on to win bronze, Turkey’s only track-and-field Olympic medal in the 20th century.

There are other heartrending stories of men and women who missed the grade narrowly and, in so doing, lost their place in the country’s sporting pantheon. Not many remember freestyle wrestler Sudesh Kumar, who in 1972 had come tantalisingly close to winning an Olympic medal.

Clearly then, success stories have been few and far between. Accounts of failure far outnumber standout Indian performances. Stories of near-misses have become even more poignant in this context, converting our Olympic journey into a tale of rued chances and laments of what could have been.

Also Read: At the Paris Olympics, the support staff won’t be there for a merry junket