Having been asked the same question for decades, Michael Holding was probably tired of it. The last wicket to fall as the shadows lengthened at Lord’s on the evening of June 25, 1983, Holding always viewed success as something cyclical. Though he was part of a legendary side that lost just one Test series in nearly two decades – and that too, in no small measure, because of some dubious umpiring in New Zealand – Holding had seen enough of life to know that no individual or team is entitled to success.

“It’s a myth that West Indies were always a strong team,” he would tell you. “When I was a youngster, we lost plenty of matches. After the great days of [Sir Garfield] Sobers, the three Ws [Everton Weekes, Clyde Walcott and Sir Frank Worrell], [Rohan] Kanhai, Wes Hall and others, West Indies went through a phase where there were hardly any fast bowlers. Just look at the team Sunny Gavaskar made his debut against in 1971.”

What Holding does accept, however, is that West Indies’ fall from grace has been especially steep. Nine World Cups have been played since 1983, and West Indies have reached the semi-final in just one of them. Back in 1996, they seemed headed for the final, but Shane Warne reopened some old wounds against leg-spin to script a last-gasp victory for Australia in Mohali.

One semi-final in 40 years. That’s as many as Kenya, who aren’t even part of the World Cup Qualifier this time. In that period, Sri Lanka – a team that West Indies skittled for 55 in a Sharjah ODI in 1986, with Courtney Walsh taking 5-1 – have reached three finals, winning in 1996.

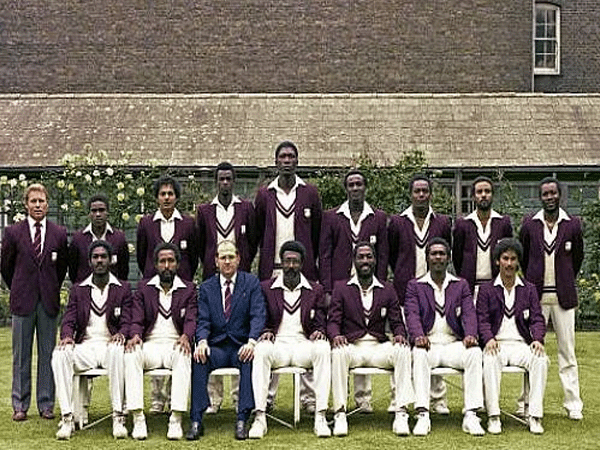

India didn’t just win the World Cup in 1983, they also shattered the aura of invincibility that West Indies had. Though they would continue to dominate Test cricket for another decade, the cracks in the edifice first became visible in the 50-overs arena. At the Benson & Hedges World Championship of Cricket in Victoria in 1985, which India won by going unbeaten through the tournament, West Indies were comfortably beaten by Pakistan in the semifinal. It wasn’t demonic pace or mystery spin that undid them either, but the medium-pace duo of Mudassar Nazar and Tahir Naqqash. With the bat, Rameez Raja and Qasim Umar saw off the best that Holding, Malcolm Marshall and Joel Garner could summon up.

Andy Roberts, the original pace great from the 1970s, had already retired by then. Garner and Holding would soon follow. Though he would play on into the 1990s, Marshall, who sadly left us nearly a quarter-century ago, would play no part in the 1987 World Cup. In more ways than one, an era had passed.

What has gone wrong since? There are dozens of theories. The lure of basketball and football is a popular one. As is the administrative chaos that has frequently troubled cricket in the region. Ian Bishop, part of the last great West Indies sides in the 1990s, has a more prosaic explanation.

“When we started playing, almost every club had one Test player or former Test player,” said Bishop. “Obviously, they wouldn’t play too many games, but when they did, you learned so much. It wasn’t just on the field either. You’d sit with them after games, and soak up whatever they had to say. The best players no longer have the time or inclination to play club cricket, so the transfer of knowledge doesn’t happen.”

It’s a viewpoint that Holding also agrees with. “It wasn’t even just Test players,” he would tell you. “Each club side had senior players who had immense knowledge about the game. It could be a pace bowler or a spinner giving you batting tips, but they had been around long enough to know the game inside out.”

Back in 1960, not long after Collie Smith had been tragically killed in a road accident in England – Sobers had been at the wheel – Worrell decided to play a season of club cricket for Boys Town, which had been Smith’s team. They won the title that year, and the young men who played alongside him never forgot the experience of walking out alongside one of the greatest figures in the game’s history.

That was the fabric from which those decades of domination were weaved. It no longer exists. Sometimes, you wonder how much Kapil Dev and his team contributed to the unravelling.