There is great anticipation and excitement, as indeed there must be, as we prepare to find our favourite spots to track the World Test Championship final between two top-notch squads from Australia and India at The Oval, London, from Wednesday. Yet, while the focus remains largely on the present, it is hard to stop the mind from diving into the past.

Each time a World Test Championship Final is played, I cannot help but recall the first time I browsed through the collection of clippings from Sport & Pastime magazine kept by N Ganesan, my sports-journalist father. It was in those pages that I discovered that the idea for the World Test Championship had first been floated by SK Gurunathan, noted cricket writer in the post-independence years, as early as 1962.

Of course, it cannot be overlooked that between May and August, 1912, England hosted Australia and South Africa in a triangular tournament of nine Tests. The series, featuring the only Test playing sides of the time, was deemed a failure with rain making its presence felt and the matches between a weakened Australian squad and South Africa not attracting crowds in England.

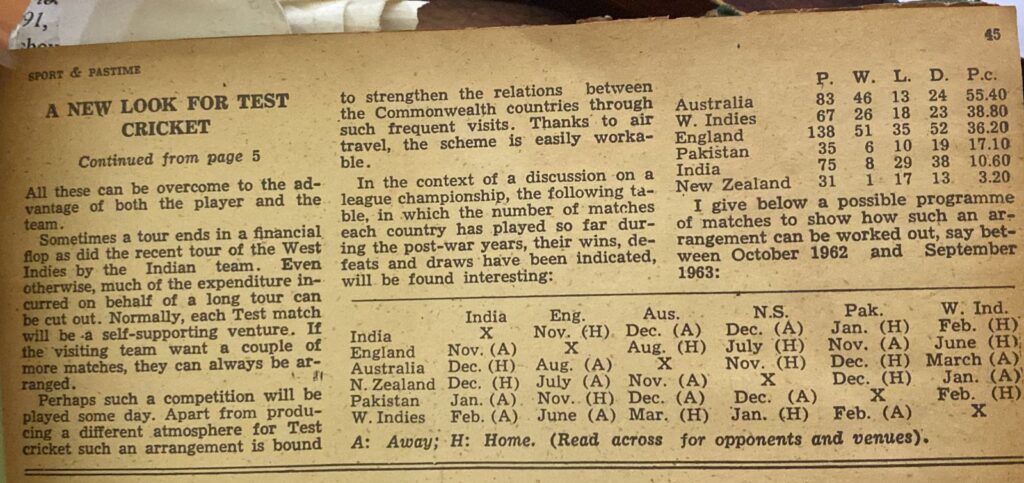

Writing in the June 9, 1962 issue of Sport & Pastime, Gurunathan suggested a programme of Test matches in which all teams would meet on a league basis, to help spot the real cricket champions of the world. He even designed a schedule in which all Test-playing teams, barring South Africa, would play one another between October 1962 and September 1963.

“Since Test matches have come to stay, would it not be a better arrangement if each team plays the others once a calendar year on a league system rather than the present arrangement in which the exchange of visits between any two countries takes place after the lapse of many years?” he wrote.

Gurunathan’s six-team, 15-match plan

“The plan I have in mind is that the six countries (I have purposely omitted South Africa), England, Australia, West Indies, India, Pakistan and New Zealand compete for a World Championship, each playing the other either at home or away between October of one year and September of the next,” Gurunathan wrote.

“This arrangement should make the competition highly interesting both from the players’ as well as the public point of view. It will be possible for the best players of each country to play against one another frequently. A true assessment of the merit of each player can be had. And when points are given for various results as in the English county championship, the champion country will emerge.

- Also Read: Virat Kohli and the Missing One Percent

“In many ways, a programme of this kind should meet the demands of modern Test cricket. Already there is a cry for short tours. After all is said and done, the purpose of a tour is to play Test matches. At least it is so nowadays. Gone is the time when a long tour had propaganda value. On a long tour, it is found that not all players are able to keep fit. Many suffer from injury of one kind or the other while quite a number of good players are not available for a tour as their employment would not permit absence over a long period.

“Perhaps such a competition will be played some day. Apart from producing a different atmosphere for Test cricket, such an arrangement is bound to strengthen the relations between the Commonwealth countries through frequent visits. Thanks to air travel, the scheme is easily workable.”

Suggestion sparks diverse reactions

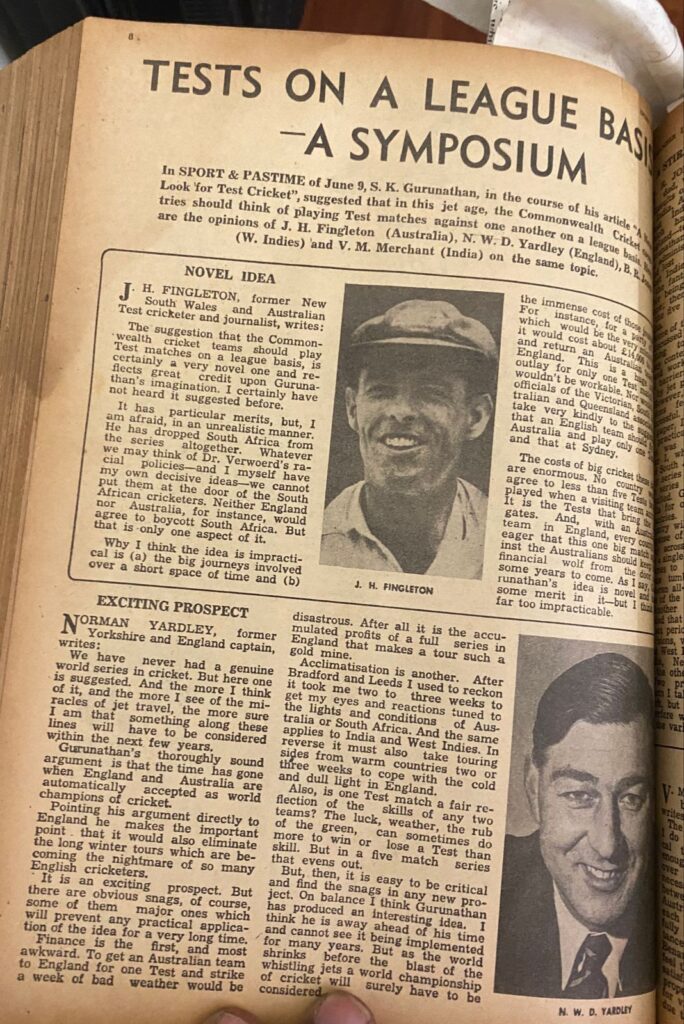

As a follow-up to his suggestion, the September 1, 1962, issue of Sport & Pastime published a compilation of opinions from former Australian Test opener Jack Fingleton, himself a journalist of repute, former England captain Norman Yardley, West Indian writer Brunell Jones and former India opener Vijay Merchant.

Stating that he had not heard the idea before, Jack Fingleton credited Gurunathan’s imagination but said that while the idea had merits, it was impractical. Besides the suggested boycott of the South African cricket team, Fingleton believed the immense costs of the long journeys by air to play only one Test match made the idea impractical.

Yardley wrote that Gurunathan had produced an interesting idea, but stated finance and acclimatisation as snags. “I think he is way ahead of his time and I cannot see it being implemented for many years,” he wrote. “But as the world shrinks before the blasts of the whistling jets, a world championship of cricket will surely have to be considered.”

Brunell Jones wrote that while former cricketers considered the plan workable because the travel barriers had been removed, administrators felt the suggestion of one-off Tests at each venue was fraught with the risk of rain interference.

“Which country will be willing to risk the expense of bringing a team halfway across the face of earth for a single game and when the time comes to play that game, rains come tumbling down?” he quoted a veteran all-rounder who sat in one of the administrative chairs as asking.

Merchant wrote that while the suggestion to have a World championship was good, he did not believe it to be practical. “Besides there is enough interest in Test matches all over the world and no such incentive is necessary,” he wrote. “I feel that the present system is quite satisfactory except that there is not proper allotment of Test matches for various teams. That may be due to financial considerations.”

Now, many years later, Gurunathan’s idea has found resonance, and we are about to experience the second ICC World Test Championship Ffinal. Unlike the 1912 tournament that drew few fans to matches not featuring the home team, you can be sure that The Oval will be packed with fans supporting India and Australia.