It was May 21, 2009. A lofted off-drive from Manish Pandey landed right in front of the media enclosure. That sixer made him the first Indian to score a century in the Indian Premier League. Fittingly, it happened at a venue called Supersport Park in Centurion, next to Pretoria, the administrative capital of South Africa.

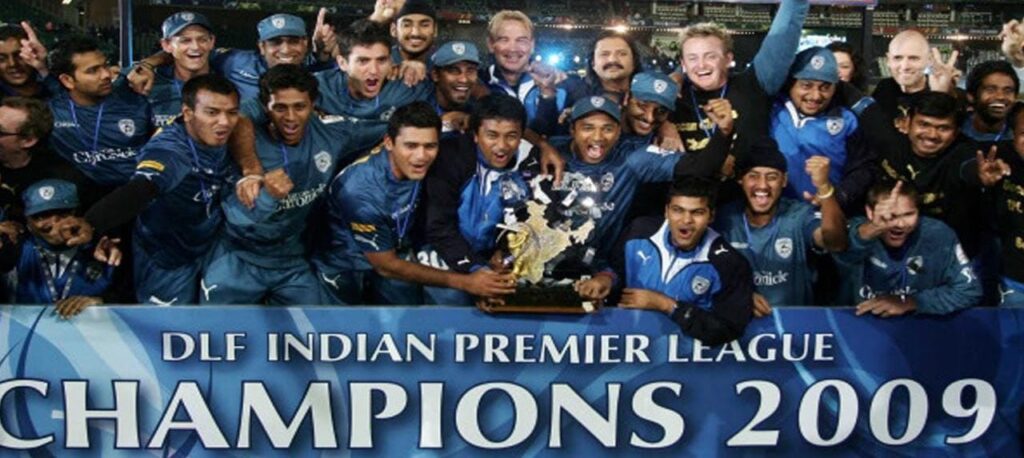

Because of that effort and due to the stupendous response the IPL got in South Africa on a whole, it became a global brand. It was a nascent concept until then. It had received a great response and TV ratings in 2008. But it was not established yet. The second edition of the event was held in South Africa because it coincided with the general elections in India. It was a super hit, just as it is now.

In many ways, this was a breakthrough moment. Not the Pandey century, but the event drawing that kind of tumultuous response in an alien country. Almost all matches were played in front of packed stands. Non-resident Indians turned up in large numbers and so did South Africans and people from other nations residing in that country. It was madness, something to be seen to be believed. Even the road shows attracted so much attention!

I had no idea what it was going to be like when I landed in Cape Town for the first match. The ground, then known as Newlands, is located right next to a beer factory and offers a spectacular view of the Table Mountain. A huge, black coloured dog entered the field of play and held up proceedings for some time during the inaugural match featuring Chennai Super Kings and Mumbai Indians. That was some start, completely anti-climactic.

Year-long Franchise Deals Point to Cricket’s Future

The response of the locals was quite something. Yes, the BCCI and the IPL governing council then headed by Lalit Modi had made arrangements to have a local connect. But the way they received the tournament was quite unbelievable. They got so involved. This holds true even now in India, where the 1000th IPL match is played today. It did not start in South Africa, but that is where its true potential as a global blockbuster was seen. The rest, as we all know, is history.

South Africans are crazy about sports. There was racial discrimination when I was there in 2009. It was not overtly visible, but felt. That, however, did not diminish the country’s affection for outdoor activities. On the streets, one would see men and women of different ages running, jogging and cycling. They, as a country, are mad about sports. And so many sports. Be it rugby, football, cricket, tennis, golf, athletics, swimming, they are everywhere.

This reminds me of a conversation with a local in Durban. Not a sports professional, he kept me asking about Indian sports, like what had caused the rift between Leander Paes and Mahesh Bhupathi, the rise of Sania Mirza, the progress of Jeev Milkha Singh, the phenomenon called Viswanathan Anand, and Bhaichung Bhutia, other than cricket. I was astounded by this person’s knowledge of Indian sports.

I am not trying to say that IPL is what it is because the second edition took place in South Africa. But I have no doubt that the event happening there made it an international spectacle. On the momentous occasion of the 1000th match, it has to be acknowledged that the acceptance the IPL has now has a lot to do with the 2009 version being staged in another country. That made it a brand across the cricket-playing world and heralded the beginning of an era that changed world cricket.