On June 26, 1983, a day after India won the Prudential Cup, The Telegraph published the following report: ‘West Bengal Congress (I) MLA, Mr Rajesh Khaitan has urged the Indian Cricket Control Board President Mr NKP Salve to press for holding the next World Cup cricket tournament in the country. In a statement here, Mr Khaitan said Mr Salve’s initial response to the suggestion was “favourable” and he had agreed to “positively take up the matter”.’

Reflecting on this dream, Raj Singh Dungarpur, one of the country’s foremost cricket administrators, wrote in his foreword to NKP Salve’s The Story of the Reliance Cup, ‘It was like a cricket utopia at the time. The concept was well beyond the Western world’s imagination that India and Pakistan could jointly hold the World Cup. The ICC was no exception.’

The organisation of the 1987 tournament was the first indication that the subcontinent was no longer content to play second fiddle to either England or Australia. India and Pakistan, in a rare show of unity, out-voted England 16–12 at the ICC general body meeting on July 19, 1984, successfully moving the 1987 World Cup to the subcontinent.

This was a big moment, evident from the following comment by Salve: ‘(This) would virtually threaten more-than-a-century-old era of England’s supremacy in the administration of international cricket. The Mecca of cricket all these long years had been Lord’s. If the finals of the World Cup, the most coveted international cricket event, were played at any other place, it would shake the very foundation on which the super edifice of international cricket administration was built.’

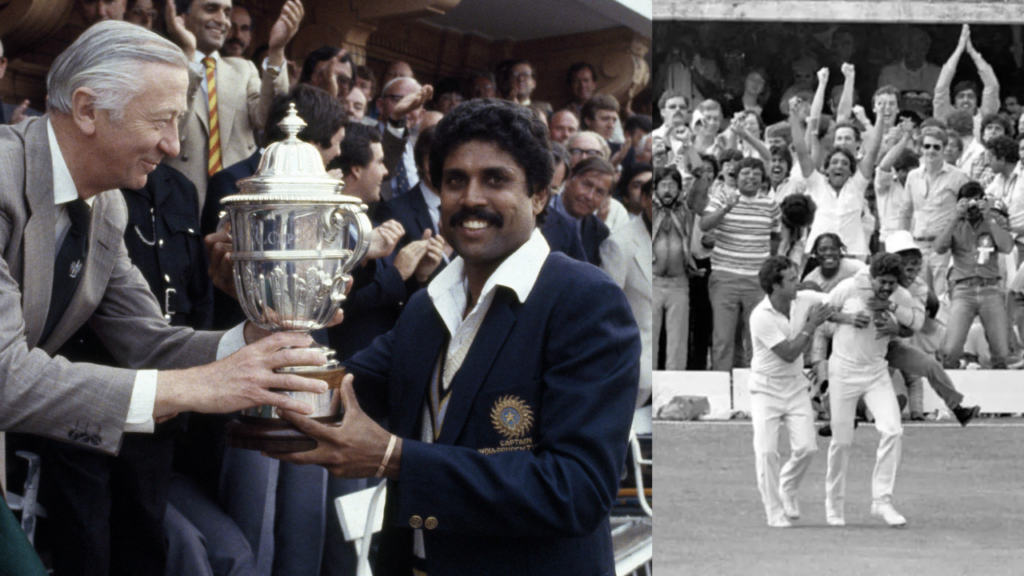

Soon after the euphoria of India’s Prudential World Cup triumph had subsided, Indian and Pakistani cricket administrators started working on a bid considerably better than England’s proposal for the 1987 tournament. The bid was drafted by Jagmohan Dalmiya, then treasurer of the BCCI, in consultation with other Board members. Its highlights were:

A minimum guarantee of £200,000 was offered to the seven participating Full Members, and £175,000 to the qualifying associate member. By contrast, England offered £53,900 plus inflation (between the 1983 World Cup and the date of payment) for Full Members, and £30,200 for the qualifier.

India and Pakistan offered £20,000 to each Associate Member while England set aside only £ 11,666.

The aggregate prize money offered was £99,500. England came up with only £53,000.

Though the financial package offered by India and Pakistan was significantly better, the English, with support from Australia, tried their best to thwart the Asian bid. Invoking rule 4(C) of the ICC’s rulebook—‘Recommendations to member countries are to be made by a majority of Full Members present and voting, and one of which in such a majority should be a Foundation Member’—the Test and County Cricket Board argued that the Indo-Pakistani bid should be rejected because it did not have the support of either Foundation Member, England or Australia. However, the ICC Chairman, under considerable pressure from India and Pakistan and also the Associates, announced that a simple majority was enough.

Eventually, as Salve writes: “The matter was put to vote—16 in favour of India and Pakistan, 12 in favour of England. ICC had decided to shift the World Cup from England to India and Pakistan. It was a miracle, which created history in international cricket. Perhaps for the first time, a battle had been successfully fought in ICC . . . India and Pakistan and her friends had shown England and her allies that they were no longer supreme in the matters of cricket administration, their power of veto notwithstanding. I must mention here that the voting was not based on the pattern of whites or non-whites because countries voting for India included Holland and Canada.”

Also Read: “Only a Matter of Time Before India Win a Big Tournament”: Clive Lloyd