KD Jadhav’s bronze-medal winning effort in wrestling never found a first-page mention in leading newspapers in 1952. The celebrations were muted and were restricted to the sports pages, which were often inconsequential and insignificant. Only the men from his native village, who escorted him with a cavalcade of over 150 cows, gave him a memorable reception.

In contrast, Leander Paes’ effort in 1996 was perceived as a ‘national’ triumph, one that was celebrated nationwide amid all classes and vocations. In terms of significance, an Olympic medal in the 1990s appeared to matter much more than in the 1950s when sport was at an all-time low on the national list of priorities. This was yet another reason why athletes who failed to win medals rarely found a mention in India’s nationalist history.

Also, hockey had captured the nation’s imagination in such a manner that other sports, team and individual, were not given due recognition. To drive home the point, while there were a series of celebrations countrywide when the hockey team returned in triumph after the Helsinki Games in 1952, Jadhav’s efforts were hardly given due acknowledgement. The political class, which celebrated hockey as a potent symbol of nationalism, did not treat Jadhav with similar respect even after he had won the first individual Olympic medal for independent India.

So near, yet so far 🏅💔

Reminiscing Deepak Punia’s heartbreaking moment at the Tokyo Olympics.

A controversial decision by the referee shattered Deepak’s hopes of a medal at the showpiece event. @FederalBankLtd @BoriaMajumdar @deepakpunia86 @Olympics #Paris2024. pic.twitter.com/1K8SoKQ9OQ

— RevSportz Global (@RevSportzGlobal) July 15, 2024

This explains why Jadhav’s family had to wait until 2001 for him to posthumously receive the Arjuna award for lifetime contribution to Indian sport. He had to build a rather modest cottage by selling his wife’s jewels in his lifetime. Hockey’s lasting nationalist significance since the 1920s was the principal reason behind such differential treatment. Politicians and sports administrators wanted to join the hockey bandwagon, just as people today are desirous of getting into the cash-rich Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI).

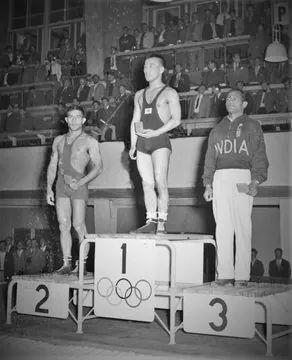

Having said that, Jadhav was surely among independent India’s early heroes, barring the hockey gold-medal winning teams. At Helsinki in 1952, Jadhav started the competition in terrific form, winning all his early bouts. Such was his performance that he was assured of a medal even before he fought his last two fights on July 22. Whether or not complacency had crept in, history will never know. What is known is that had Jadhav not lost both of those bouts, he would have managed a higher podium finish.

This is how the Times of India celebrated his achievement: ‘History was created here today when India, who has been competing in the Olympic Games since 1924 gained a place in the individual honours list for the first time through K.D. Jadhav, the bantamweight wrestler, who won a bronze medal. Although Jadhav was today beaten by Russia’s Roshind Mahmed Bekov (gold medal) and Japan’s Shihii in a points decision (silver medal) he gained his place with a series of brilliant bouts during the last week.’

The newspaper went on to describe Jadhav’s bout against the Russian in detail, “Although Jadhav was aggressive and a good trier, able to equal the formidable Russian’s skill he was unable to match his strength and this weighed the scales against him. The Russian won all three periods. In the first Jadhav jerked him down but was himself twisted over in falling and narrowly escaped a fall. Bekov had the Indian in difficulties after that but Jadhav always wriggled clear.”

What made Jadhav’s performance all the more significant was that the rules at international contests were different from those followed in India. While Indian wrestlers were used to winning simply by putting their opponents flat on their backs, international rules specified that the opponent had to be pinned for two seconds on the canvas with their shoulders touching the mat before a fall verdict could be declared.

Jadhav had learnt of this rule in London four years earlier when Rees Gardner, the US lightweight champion, who had trained the Indian wrestlers for a week before the Games, coached him. In London, Jadhav had finished sixth in a field of 42. Jadhav is now a forgotten man in the annals of Indian sport, but his story is one of true grit and resilience.

Also Read: Paris is yet one more challenge for Pullela Gopichand