Trisha Ghosal at Eden Gardens

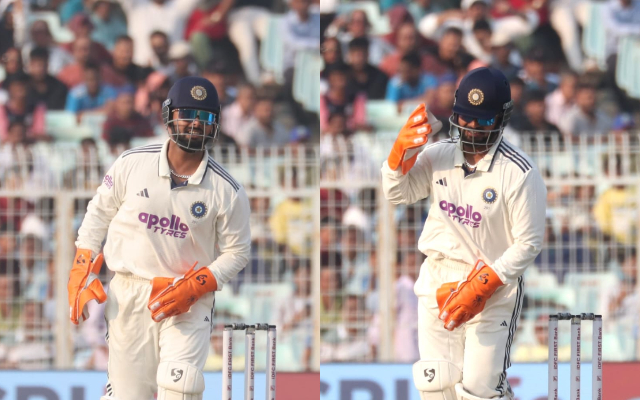

On the second day of the opening Test against South Africa, the Indian dressing room carried an unexpected ripple: Shubman Gill would not take the field. For a team defending a slender lead of just 30, this was far from ideal. The responsibility of shepherding India through South Africa’s second innings, on a pitch that had clearly woken up cranky, fell squarely on the shoulders of vice-captain Rishabh Pant. And what followed was a masterclass in proactive, unfazed, deeply instinctive leadership.

Pant’s cricketing mind has always been engrossing, a blend of audacity, clarity, and a refusal to be boxed into conventional rhythms. On Saturday, those instincts were on full display. India needed early breakthroughs. They needed discipline. They needed creative thinking. Pant delivered all three.

His field settings alone told a story of a captain determined to stay on the front foot. When he urged Kuldeep Yadav to go round the wicket, it wasn’t a routine adjustment; it was a subtle shift in angle that worked instantly. The attempted wrong ’un held its line, Marco Jansen top-edged a slog-sweep, and KL Rahul completed the catch, with just one slip and five men guarding the fence. It was calculated, not conservative.

For More Exciting Articles: Follow RevSportz

Axar Patel’s change of ends, accompanied by a slip and a silly mid-off, was another firm stamp of Pant’s mindset: pressure is a tool, not an outcome. In Kyle Verreynne’s case, the tightening of the noose was exquisite. Pant set the same attacking cordon, slip and silly mid-off, and within ten balls, the South African wicketkeeper cracked, attempting an ill-judged release shot that only hastened his departure. For de Zorzi, Pant doubled down further: slip, leg slip, short leg, Jadeja round the wicket. No breathing room. No easy singles. No mental space. Two balls later he was back to the hut.

It wasn’t just the fields. The decision to place Dhruv Jurel at second slip, ahead of the more obvious choice in Devdutt Padikkal, showed the clarity with which Pant thinks. A keeper understands deviation better than anyone else; Jurel’s ability to sight and anticipate made him an inspired fit for the role. Pant recognised that instantly.

Even more impressive was his composure with the Decision Review System (DRS), often a graveyard of emotional captaincy. On a surface where every ball seemed to thud into the pad, bowlers were understandably excitable, rushing to Pant after every denial from the umpire. But Pant trusted what he saw. Sitting behind the stumps, he had the best vantage point, and he refused to be swayed by emotion or the pressure of collective appeals. Time and again, he got it right.

To call this a complete assessment of Pant’s Test captaincy would be premature. The sample size is tiny, the pitch was loaded in favour of bowlers, and South Africa contributed generously to their own downfall. There were no long partnerships to truly challenge his patience or tactical longevity.

But what we did see, unmistakably, was a captain who mirrors his batting persona when given control: he takes the bull by the horns. He creates chances, he nudges the game forward, and he refuses to let the match drift. Pant is not a leader who waits for something to happen. He is a leader who makes things happen.

And if this was merely a glimpse of his captaincy future, Indian cricket might just have found a skipper with imagination to match his nerve.

Also Read: Can Eden Gardens Recreate The Oval’s Final-Day Roar?