Fast bowlers hunt in pairs. From the early years of international cricket to the T20 era, this has been more rule than exception. Almost every country has had its share of pairs, some just a few, others far more. No point in taking names, since there so many, from Larwood-Voce in the black-and-white era to Boult-Southee in modern times.

India did not really have a pair of their own for a very long time. There were Mohammad Nissar and Amar Singh when India started playing Tests in the 1930s. After that, the country had to wait well into the new millennium for what could well and truly be called a pair or a pack of fast bowlers. Bowlers of this generation hunt as individuals, in pairs and, sometimes, as a team of three or four. But if one looks at the gap, it is fairly long.

There is one pair of medium-pace bowlers not often talked about when this subject is discussed. They did not operate together for a long time, that’s one reason. That they were too reliant on conditions is another. They were overshadowed by a towering personality at his peak when they were regulars in the XI – that’s the third reason.

Unlikely backbone of the attack

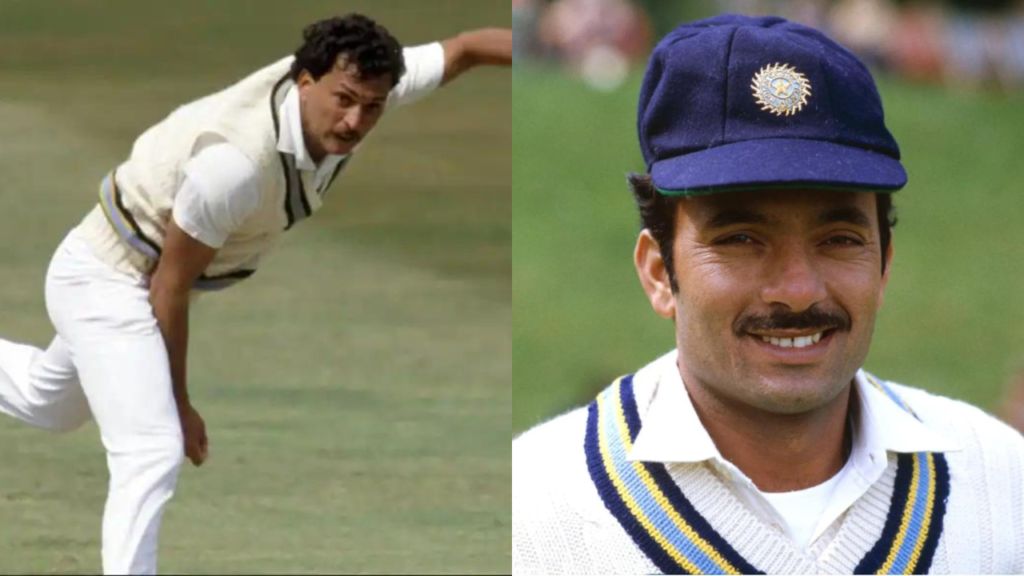

One could also add that Roger Binny and Madan Lal did not form the commonest of pairs in the sense that the two of them rarely shared the new ball. But they formed the backbone of the Indian attack when Kapil Dev’s team shocked the world in 1983. Kapil’s 175 not out against Zimbabwe will remain the talismanic performance of that campaign, Mohinder Amarnath’s Player of the Match awards in the semi-final and final will be glowingly talked about, and so will Kapil’s catch to send back Viv Richards in the final.

Not everyone remembers that it was a miracle based mainly on the blows inflicted by the Indian bowling unit. Binny topped the list of bowlers with 18 wickets from eight matches. Madan Lal was joint-second with 17. Kapil was next among Indians, with 12 scalps. After his 175 not out, Australia was another must-win last league match for India. Binny and Madan Lal took four apiece to help bundle out the opposition for 129.

Crucial contributions throughout

Binny was Player of Match in this crucial encounter with figures of 8-2-29-4. Madan Lal, who returned 8.2-3-20-4 in that game, claimed three more in the final including the big wickets of Richards and Desmond Haynes. In the first-leg league outing against Zimbabwe, he was the Player of Match. Binny was not spectacular in the semi-final or final, but had combined figures of 22-1-65-3 from those two games. It shows how effective they were at different stages of the World Cup.

In typically English conditions, these two were vastly different than they were in the sub-continent. Neither had pace, Madan Lal even less so, but when the ball did a bit or more in the air and off the pitch, they were more than handy. In 1983, both were experienced and bowled where they wanted to or the captain needed them to, with unerring accuracy. Swing has always excited bowlers like them. To make the most of it, bowlers must find the right length and keep landing the ball on the spot they have found. Binny and Madan Lal did that consistently over three weeks.

Odds they had to overcome

Another oddity about this duo was that they did not always get the new ball. Those who hunt in pairs usually open the bowling. In 1983, it was mostly Balwinder Singh Sandhu doing that job with Kapil. He will be remembered for getting Gordon Greenidge to fatally shoulder arms in the final. Binny and Madan Lal took over after Kapil and Sandhu had finished their first spells.

This made their task more challenging. They had to operate in a period of the innings when the fifth medium-pace option, Amarnath, would also come into the equation. There would be occasional spin and the new-ball bowlers coming back for second or third spells. Matches being 60 overs a side back then helped Kapil, as captain, to spread things out to an extent. Still, the team owed a lot to Binny and Madan Lal for understanding their roles and requirements promptly, and performing accordingly.

It was not easy to deliver under a personality like Kapil. No matter how the others fared, he would always remain the spearhead of the attack, no doubt for valid reasons. So the job of the others was essentially to play the second and third fiddle. They would never be at the forefront. To realise this and optimally use the opportunities they got required the ability to wait patiently, and hit the straps immediately on being handed the ball. That’s why no praise is enough for the collective performance of Binny and Madan Lal in 1983.

Three years later, these two came together in England again, albeit for a short period. In the first part of the English summer in 1986, India won the three-Test series 2-0. Binny took 12 wickets. Not part of the squad, Madan Lal was plucked out of the Lancashire league to replace an injured Chetan Sharma in the second Test. He responded with five wickets, including 3 for 18 in the first innings. It proved that 1983 was no fluke. These two were underrated, yet made for each other in conditions that suited their kind of bowling.

- More: The significance of 1983