Indian-origin journalists like Dicky Rutnagur and Mihir Bose were fixtures on the pages of British broadsheets for decades, right from the mid-1960s. But for the longest time, the narrative around cricket, especially that played in India or by Indians, was on the lines of colonial master-and-native stereotypes. At times, the condescension was blatant. Sometimes, it was well-veiled. But it was almost impossible to read through a copy on Indian cricket without stumbling across a stereotype or three.

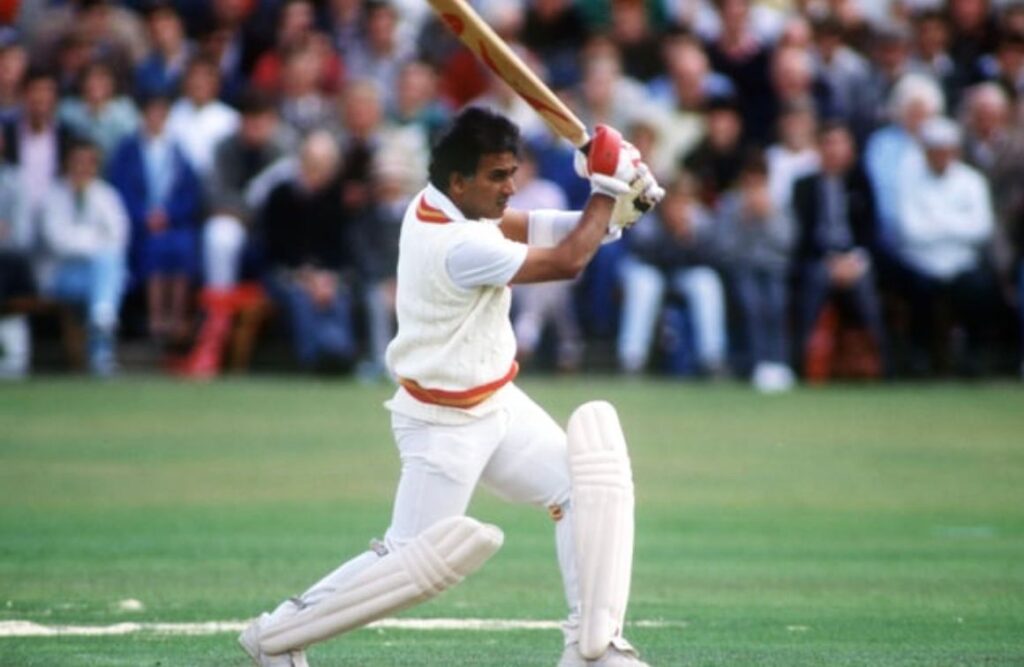

For whatever reason, journalists based in India did little to bust these myths. Perhaps they felt their words lacked the heft to take on the EW Swantons of the world. This began to change only with the advent of Sunil Manohar Gavaskar. As a young man, he seethed quietly when labels were glibly stuck to the Indian team. But as his career progressed, and he became one of the great batters of his, or any other, era, he became increasingly vocal about these long-established canards.

Indians are lazy Maharajahs who couldn’t be bothered to field properly? No, said Gavaskar. The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) was so impoverished in those days that the lush, manicured outfields of today were a mirage. Few were going to fling themselves around on mud and stones and risk a career-ending injury.

Indians cowered and ran from express fast bowling? Nonsense, said Gavaskar, who resented the idea that he was the first to buck that trend. As a schoolboy, he had listened on the wireless as Polly Umrigar batted with tremendous bravery to make 445 runs on a tour of the Caribbean (1961-62) where Nari Contractor’s career was ended by a skull fracture sustained while facing Charlie Griffith.

Like Voltaire, the French philosopher, Gavaskar suggested that others looked into their own gardens. Australia’s batters were repeatedly blitzed by the Fire in Babylon in the late 1970s and early 1980s. England suffered two ‘blackwashes’ in 1984 and 1986. No one questioned their stomach for battle.

The BCCI, with the likes of Jagmohan Dalmiya, NKP Salve and Inderjit Singh Bindra at the helm, was the devil incarnate, and would sell cricket’s soul for pieces of silver. Who started World Series Cricket, Gavaskar would ask. Which country introduced professionalism into the first-class structure? And where would cricket be without the audience and funds from the Indian subcontinent?

When Gavaskar entered broadcast booths around the world soon after his retirement, it didn’t just expose viewers to an ‘exotic’ accent, but to an altogether different mindset. Each time a stereotype was peddled, Gavaskar would push back with a firmness that was never rude – a bit like the forward defensive that he played with matchless elegance.

As his commentary career flourished, the Indian cricket media also gained in confidence. No longer did it need seals of approval from elsewhere. Visiting journalists eager to push their established and tired narratives quickly found that there would be a dozen ripostes. There was no more turning the other cheek.

Anyone who’s read this far might mistake Gavaskar for some serious activist type. He is anything but. Two or three generations of Indian journalists who have toured far and wide with him will attest to his incredible mimicry and wicked sense of humour. Even in his 70s, he won’t miss a chance to prank you, whether that’s in person or over text. At any India-Pakistan match, it is a common sight to see journalists from both sides of the border crowded around the little master and dissolving into peals of laughter as they watch his Javed Miandad imitation.

To this day, Gavaskar retains such youthful enthusiasm for the game that it’s hard to believe he’s 75 today. Most of our readers will not have watched him play. Their views will be formed mostly by what they hear on TV, where the template has veered towards non-critical sameness in recent years. But Gavaskar the man has always transcended such narrow boundaries. Long may he continue to be Indian cricket’s premier voice.