In his poignant essay on the life and times of Colin Milburn, whose career ended after he lost his left eye in an accident, Matthew Engel wrote: “Milburn might not have been the greatest cricketer of his generation, but he was, beyond question, the cricketer we could least afford to lose. And we lost him.”

As far as Indian football is concerned, Syed Abdul Rahim was the individual it could least afford to lose. And more than six decades after cancer claimed him at the age of 53, football in this country is still counting the cost. The gold medal at the Asian Games in Jakarta in 1962 could have been a springboard for more success. Instead, it became the epitaph for both a pioneering coach and Indian football.

In the world around us, democracy is something to be cherished. The Indian General Elections, which will soon be upon us, is one of the wonders of the modern world, for the sheer scale of the exercise undertaken. But democracy has no place in elite team sport. You look at the history of sporting greatness, and the narrative is peppered with benevolent dictators whose vision shaped their teams.

This is true of every sport. And, almost always, it is the coach who is that dictator. American Football’s greatest prize is named the Lombardi Trophy after Vince Lombardi, whose coaching genius took the small, sleepy Wisconsin town of Green Bay to the centre of the sporting universe.

For the Latest Sports News: Click Here

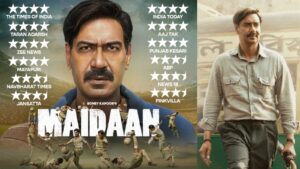

🚨Behind the Scenes || Maidaan

Selecting 11 players from 7000 faces, a year of intense training, and more – delve into the behind-the-scenes sweat, pain, and hard work that culminated in the masterpiece film, Maidaan.

@ajaydevgn #PriyamaniRaj @raogajraj @BoneyKapoor… pic.twitter.com/tN8aEAk4Kf— RevSportz (@RevSportz) April 12, 2024

If Manchester United are revered the world over today, it’s because of the teams that Sir Matt Busby built in the 1950s and 1960s. After the first iteration was decimated in a plane crash at Munich Airport in February, 1958, Busby and the club rose from the ruins. A new generation led by George Best and Denis Law joined Bobby Charlton, one of the survivors, in a side that won the European Cup – precursor to the Champions League – in 1968.

Busby’s time at United spanned 24 years, a record that would be surpassed by Sri Alex Ferguson, his fellow Scot, nearly half a century later. Across the M62 from Manchester, the foundations of Liverpool’s modern-day greatness were laid by Bill Shankly, whose 15 years in charge also involved rebuilding after his first title-winning side had begun to decay.

As Maidaan shows, with beautifully choreographed action sequences, in that 1962 Asiad, India beat both Japan and South Korea. They would beat the Koreans again two years later in Israel in the Asian Cup, as Harry Wright took the core of Rahim’s gold-medal side to second place in the continental competition. After that, the trajectory of Indian football has been a lot like a diver plunging into water from the 10m platform board.

Few publishing houses are likely to commission a work on what has happened in Indian football since the Rahim years. That’s because the chapters on the administration of the game are superfluous. They could easily be replaced with one word: rubbish, garbage or their many synonyms. Even in his day, Rahim had to deal with these self-important buffoons, whose loyalty often lay with their clubs or states and not the national flag.

When you look at where Japanese and Korean football are now, you wince. Busby, who was born the same year as Rahim, stayed in the United job till 1969. Had Rahim lived at least till the end of that decade, there’s a fair chance that he would have completed a framework that led to World Cup qualification in the years that followed.

Or maybe not. As United have discovered in the decade since Ferguson finally left, maverick geniuses are nearly impossible to replace. In a perceptive essay on the Rahim Effect in the pages of Sport & Pastime magazine, N Ganesan, whose son, G Rajaraman, is of this parish, had mentioned a little anecdote about the 1952 Helsinki Olympics.

While those back home mocked Rahim and his side after a catastrophic 10-1 defeat to mighty Yugoslavia, the coach also spent his time in Scandinavia attending coaching refresher courses in Stockholm. Sweden has a proud coaching tradition – from Nils Liedholm to Sven-Göran Eriksson – and Rahim was far ahead of his time in recognising the need to constantly evolve both tactics and training methods.

That Rahim also scouted talent from every corner of India, instead of thinking football began and ended with Kolkata’s legacy clubs, is also testament to his greatness. But while the teams that he outwitted on the way to Asian Games gold forged ahead, Indian football went backwards. Or in the more dramatic words of Fortunato Franco, one of the midfielders from the 1962 team, “With him, he took Indian football to the grave.”

These years later, we’re still struggling to dig our way out.

Also Read: Rahim Saheb was like a God to us: Arun Ghosh