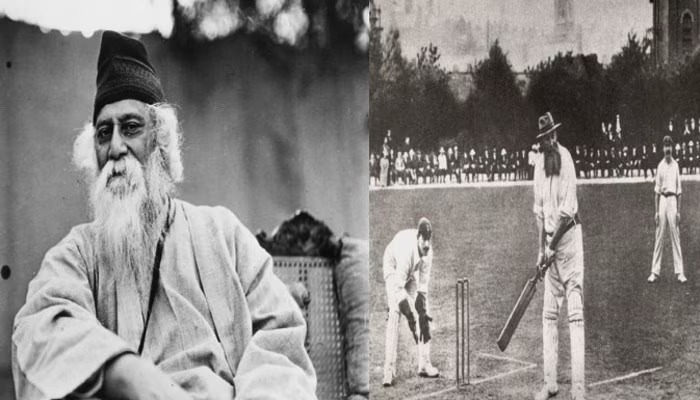

Brajaranjan Ray, the pioneer of sports writing in Bengali, once recounted his experience of having met the proprietors of the leading vernacular daily of the time, and convincing them of the necessity for sports journalism. In this unpublished essay that I had the good fortune to read, Ray had something interesting to say about Rabindranath Tagore. Apparently, he was at a loss for Bengali equivalents of English terms in describing and reporting cricket matches. And who else to turn to, but Tagore?

Tagore, of course, was as encouraging as ever. He asked him to go ahead without fear, and invent terminology. He guessed right that whatever Ray coined and persisted with, would, with the passage of time, become standard usage. Ray, of course, was free to turn to him for advice and corrections.

It is not for nothing that we Bengalis think that there ain’t no sphere the legend left untouched.

Not just that. Apart from this Ray-Tagore encounter in the 1930s, there is also an imaginary match apparently played sometime in the 30s that I’m reminded of. It was fascinatingly described in a piece – loosely translated as Rabindranath and Cricket – published sometime in the 1950s in Dainik Basumati, a Bengali journal, and later reprinted in some collections.

The setting for the match was Gomoh, a small town near Dhanbad, Bihar, more famous for the railway station from which Subhash Chandra Bose took his train towards Europe. The writer wants us to believe that Tagore had apparently gone there for a brief visit, and decided to organise the match.

The players who played against Tagore’s team included such luminaries as Vizzy, the Maharjkumar of Vizianagram; The Maharaja of Patiala, Pataudi Senior; The Maharaja of Cooch Bihar and Duleepsinhji.

They had apparently come in their private luxury vehicles, a point emphasised in the piece.

Also Read: Rabindra Jayanti, Shah Rukh’s Recitation, and 1am Walks Home

That they spent to play the game, rather than playing it to earn coin, does not need to be emphasised, but another interesting sidelight of the match described was a snippet about ads. In the 1930s, advertising was still in its infancy, but apparently not for this match. The leading sports-goods dealers from Bengal — S.Ray and Co., Uberoi et al — had all seemingly assembled in Gomoh with their range of products.

The inaugural ceremony for the match was initiated by a shehnai recital, though the Maharaja of Patiala had also, it seemed, arranged for a band to perform on the occasion. Two players from Tagore’s side, Professor Kshiti Mohan Sen (father of our Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen) and Acharya Bidhusekhar Shastri recited vedic mantras to start off the proceedings. The stadium, a temporary arrangement for the match – comparable to modern one-day internationals – was packed to capacity.

Another key aspect of the game, similar to present-day cricket, was the presence of women spectators. They were all dressed in saris worn the Maharastrian way. It is worth mentioning in this context that women in the 1930s played cricket in saris, and there was a regular tradition of cricket between men and women in Kathiawar.

Also present for this match were Mani Behn, the great dancer, Rajkumari Sharmila, the famous motor-racing specialist, the daughters of the Gaekwad family, the Rajkumari of Burdwan, and sundry other who’s who.

Needless to mention, it had to have nationalist overtones. So Tagore, inspired by swadeshi, played with a bat made from local wood, wore a toka (a headdress worn by peasants) made of palm-leaves, and was dressed in a dhoti. Now, this is not just the anonymous writer’s imagination, for cricket in dhotis was very much in vogue in the 1930s and may well be perceived as an attempt by the Indians to appropriate cricket for nationalist purposes.

The Mohun Bagan Club did this in 1930 for a match against the Governor’s XI and, upon being reprimanded by RB Lagden for their dress, refused to play. The match was eventually abandoned when Lagden refused to tender the apology demanded by Mohun Bagan.

Six months later, a similar thing happened in a match between the Vidyasagar College and the Calcutta Cricket Club.

So whether or not Tagore had much to do with cricket, we Bengalis definitely think – with evidence too – that he was involved in the genesis of cricket journalism in Bengali, and also a pioneer in the commercialisation of the game. After all, the various dynamics of commercialisation are very much in evidence in the author’s imagination. Perhaps this match could also be imagined as a precursor to the modern IPL!