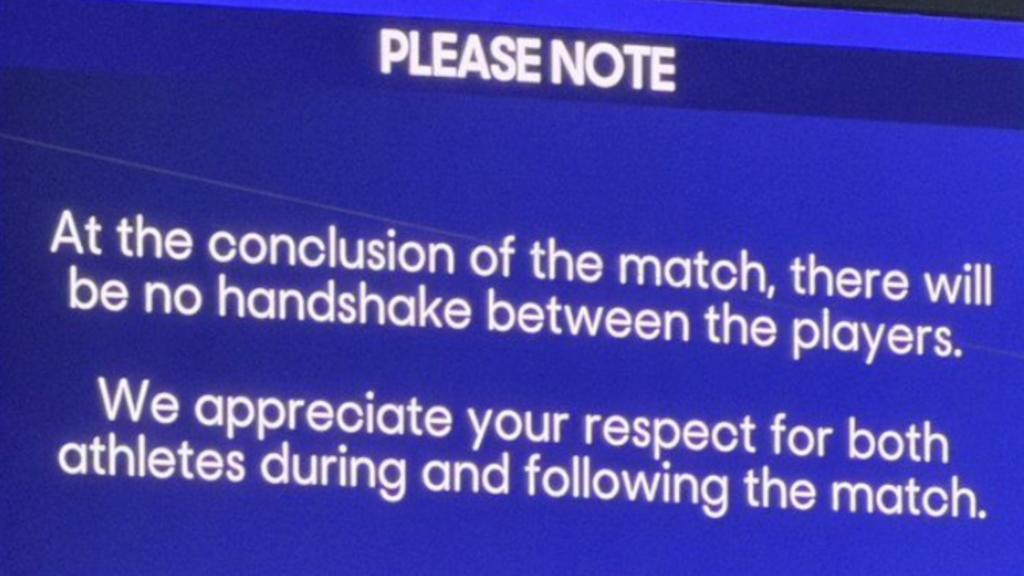

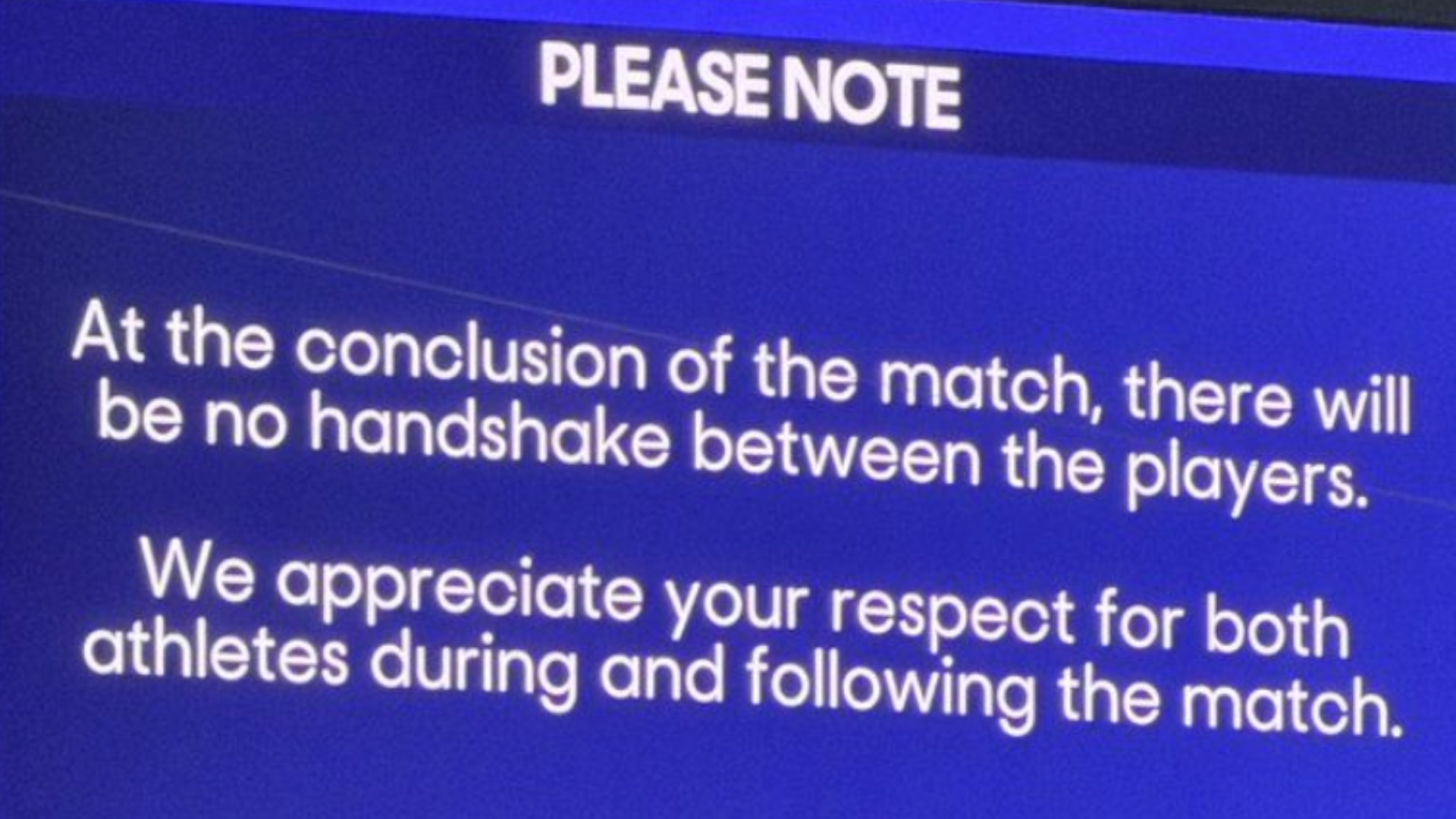

At the Australian Open, ahead of the semi-final clash between Aryna Sabalenka of Belarus and Elina Svitolina of Ukraine, a message flashed on the stadium screens: “At the conclusion of the match, there will be no handshake between the players. We appreciate your respect for both athletes during and following the match.”

There is no “long story short” when it comes to histories shaped by geopolitical tension. However, to summarise the strained relationship between Ukraine and Belarus: relations have sharply deteriorated since 2022. Russia used Belarusian territory as a key staging ground for its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Belarus allowed Russian troops, missiles and logistics to operate from its soil. Although Belarus never formally declared war on Ukraine, its deep military integration with Moscow positioned it, in Kyiv’s eyes, as an ally of Russia.

Belarus has hosted Russian forces, conducted joint military exercises, and housed tactical nuclear weapons near Ukraine’s northern border, forcing Kyiv to maintain heavy defences. As a result, the Ukraine–Belarus border has become a heavily militarised flashpoint, marked by constant tension and the persistent threat of escalation. This stance has been widely accepted, respected and contextualised.

“They have been doing it for so long, about the handshake – it’s their decision,” Sabalenkasaid after the match. “I respect that, and I respect her as a player.”

Her opponent was even more forthright. “People are living really horrible and terrifying lives in Ukraine, so I should not be allowed to be sad because I am very, very lucky,” Svitolina said after the loss to Sabalenka.

Speaking of cross-border tensions and snubbed handshakes, another pair of countries comes to mind: India and Pakistan. Recently, at the Asia Cup, India refused to shake hands with Pakistan in their first meeting of the tournament and maintained that position throughout. India’s stance was heavily criticised in global coverage of the impasse, framed as a violation of the “spirit of the game”.

The language was moralistic and accusatory. India was portrayed as politicising sport, overlooking the fact that the refusal followed a terrorist attack that claimed 26 lives. A history that includes four wars, decades of cross-border terrorism, repeated military escalation and unresolved conflict was conveniently ignored.

When Bangladesh refused to travel to India citing “security threats” – later debunked by the International Cricket Council (ICC) – India, particularly the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI), was accused of “ruining the sport”. It was insinuated that ICC had “different rules for different boards”, when in reality India has maintained its position of not engaging in bilateral fixtures and travelling to Pakistan since the 26/11 terrorist attack in 2008. The same media ecosystem that has normalised Ukraine’s sporting protest struggles to extend the same grace to India. Instead, India’s geopolitical trauma has been selectively trivialised.

A pattern emerges: European geopolitical tensions are treated as complex, grave and legitimate, while South Asian realities are flattened into spectacle. Just as at the Australian Open, the Pakistan team’s captain was informed ahead of the coin toss at the Asia Cup that there would be no handshake between the two teams. The truth is simple – when Ukraine does it, it’s policy; when India does it, it’s politics. What this asymmetry and hypocrisy reveals about international sports journalism is for you to decide.